Delight among community members as 12 more languages are added to the Georgia driving permit test

“We’ve been waiting and anticipating this”: Now beginning drivers can take the test in Haitian Creole, Rohingya, Pashto, Yoruba, and more.

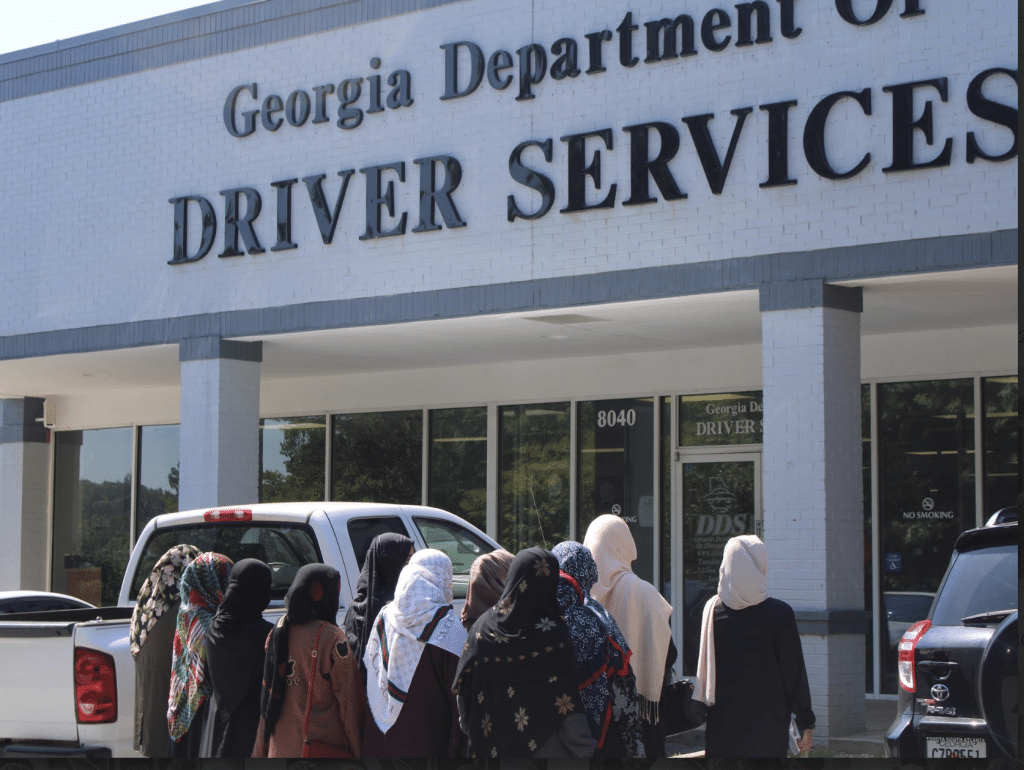

In late July, the Georgia Department of Driver Services (GDDS) made 12 additions to the list of languages available to Georgia residents taking the test to get their driver’s permit. The permit test is now being offered in Albanian, Amharic, Burmese, Haitian Creole, Italian, Pashto, Portuguese (Brazil), Rohingya, Swahili, Urdu, Wolof, and Yoruba.

“We’ve been waiting and anticipating this,” said Watson Escarment with Lawrenceville’s Good Samaritan Haitian Alliance Church, which has been offering classes that help Haitians learn English so they can pass the permit test. With the addition of Haitian Creole to the language options, “there are numerous people that we know that can benefit,“ Watson said.

For those who speak limited or no English, passing the written permit test is the first and primary hurdle to driving independence in car-centric metro Atlanta.

The recent update means that the permit test is now being offered in 26 languages in all. (See the full list here.) GDDS spokesperson Susan Sports told 285 South that the department reviews data several times a year to see how many requests have been made for tests in different languages. “If a language is only requested once or twice a year, we would not likely add it to the translated test list,” she explained. But if the demand is greater, the department may opt to translate the test into that language. Pashto, for instance, “was one of the languages where there was a high demand for interpreters, which is why it was included.”

Previously, if somebody who spoke only Pashto wanted to take the permit test, they would have to first take it in English. If they failed, they would be able to request a Pashto interpreter, said Sheela Poya, a case manager for the Afghan American Alliance of Georgia. Every month, Sheela and her colleagues take members of the Afghan community to the GDDS location in Lithonia for their permit and driving test, requesting appointments with Pashto interpreters as needed. Now, with the tests available in that language, a bureaucratic step has been removed—and community members can get on the road more quickly, Sheela said: “When they cannot drive, they cannot find a job. When they cannot drive, they cannot go to the doctor. So, it’s very important for our community.”

For Ayub Mohammed, president of the Burmese Rohingya Community of Georgia, the additional languages mean more than just the removal of a practical barrier. When he first saw Rohingya listed on the GDDS website, “I felt a deep rush of emotion,” he said, for the Rohingya people—who have been “denied and erased,” with thousands killed in Burma and nearly one million displaced. Seeing their language “recognized so openly,” Ayub said, “felt like the world was finally saying: ‘We know who you are, and we cannot erase your truth.’”