A 1996 documentary explored how immigrants were changing Atlanta. Thirty years later, it’s still resonant.

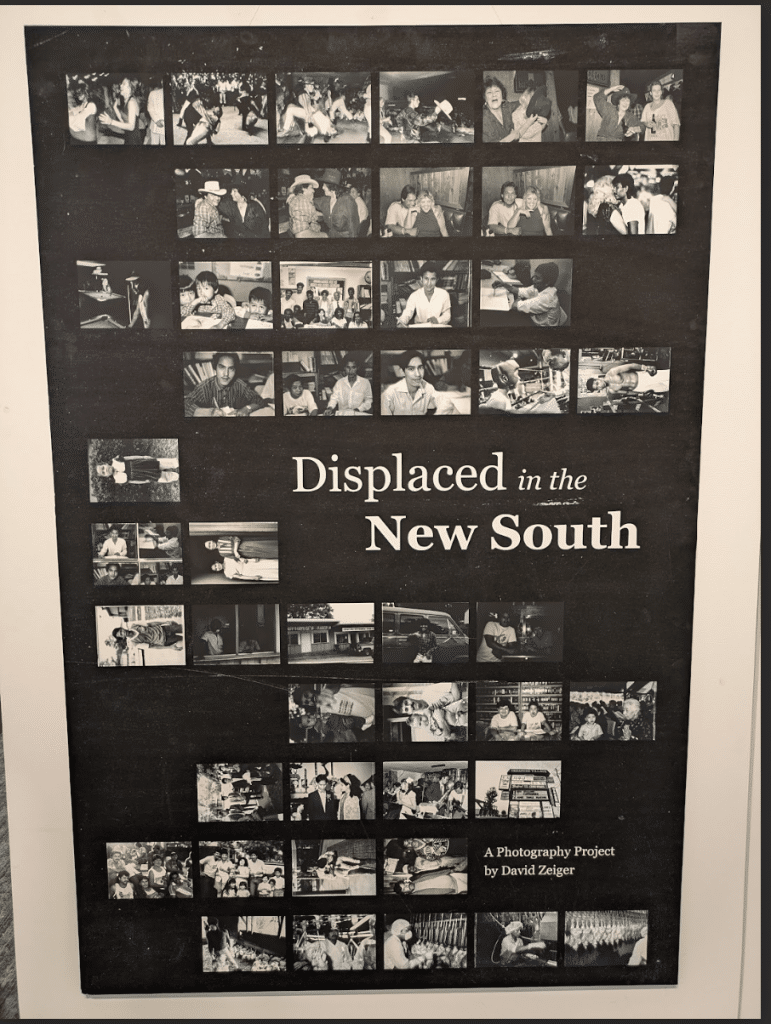

Photos from David Zeiger’s Displaced in the New South are the core of a new exhibit at the University of Georgia.

The footage shows the aftermath of an immigration raid in Georgia. Individuals tell the camera how agents entered the factory without warning, pulling everyone with Spanish surnames off to the side for interrogation. The camera lingers on the plastic zip ties binding people’s hands as they’re forced to stand in line, awaiting transport to an unknown destination.

In 2025, these images of state violence may be chillingly familiar. But the footage is from 1993. It was recorded at a moment when documentarian David Zeiger was filming the rapidly shifting ethnic landscape in northern Georgia for his film Displaced in the New South.

Zeiger was making the documentary at a time when waves of immigration from around the world—particularly Asia and Latin America—were reshaping the social and economic landscape of Atlanta and beyond. Simultaneously, anti-immigrant sentiment and state repression were also increasing nationwide, leading to scenes like the workplace raid Zeiger filmed at a plant in Gainesville.

Today, when one in ten Georgians is foreign-born—and immigration continues to fuel Atlanta’s growth—the film reminds us of a critical moment in the evolution of the state’s demographics and subsequent strengthening of immigration enforcement mechanisms.

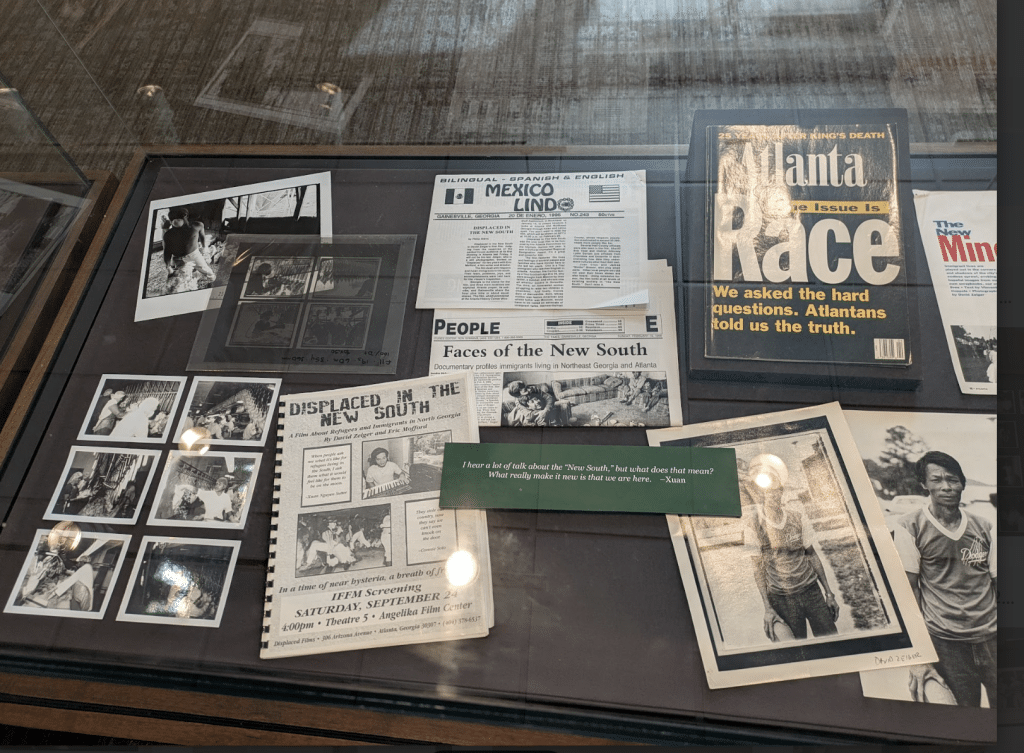

Its enduring relevance, particularly at another moment of rising anti-immigrant sentiment, is one reason it’s being revisited in Displaced in the New South: A Photography Project by David Zeiger, an exhibit on display through December at the Richard B. Russell Library on the campus of the University of Georgia in Athens. Both then and now, Zeiger has endeavored to produce work that could, “in a time of near hysteria, [offer] a breath of fresh air.”

Prior to making Displaced, Zeiger was an organizer with the movement opposing the Vietnam War. Originally from Los Angeles, he moved to Georgia in the 1970s and found work in Cabbagetown, though he lived in Chamblee. After leaving for Detroit for a few years, he returned to Georgia in the late 1980s. Immersed in Atlanta’s theater world, he also took up a passion for photography, shooting work for local arts organizations and publications like Atlanta magazine.

Originally interested in documenting white flight in places like Chamblee and Doraville, he instead found that something else was going on: The neighborhoods where he had once lived alongside other primarily white, working-class people were increasingly home to migrants from Asia, the Caribbean, and Latin America.

“The local cowboy bar, Mustache Mike’s, was now Mustacho Miguel’s,” Zeiger reflected in a recent artist’s statement. “The apartment complex I had lived in was now home to immigrants from Vietnam, Korea, and Laos; an old warehouse outside of I-285 had been transformed into the International Ballroom . . . and the old run-down shopping center was now the vibrant Chinatown Mall.”

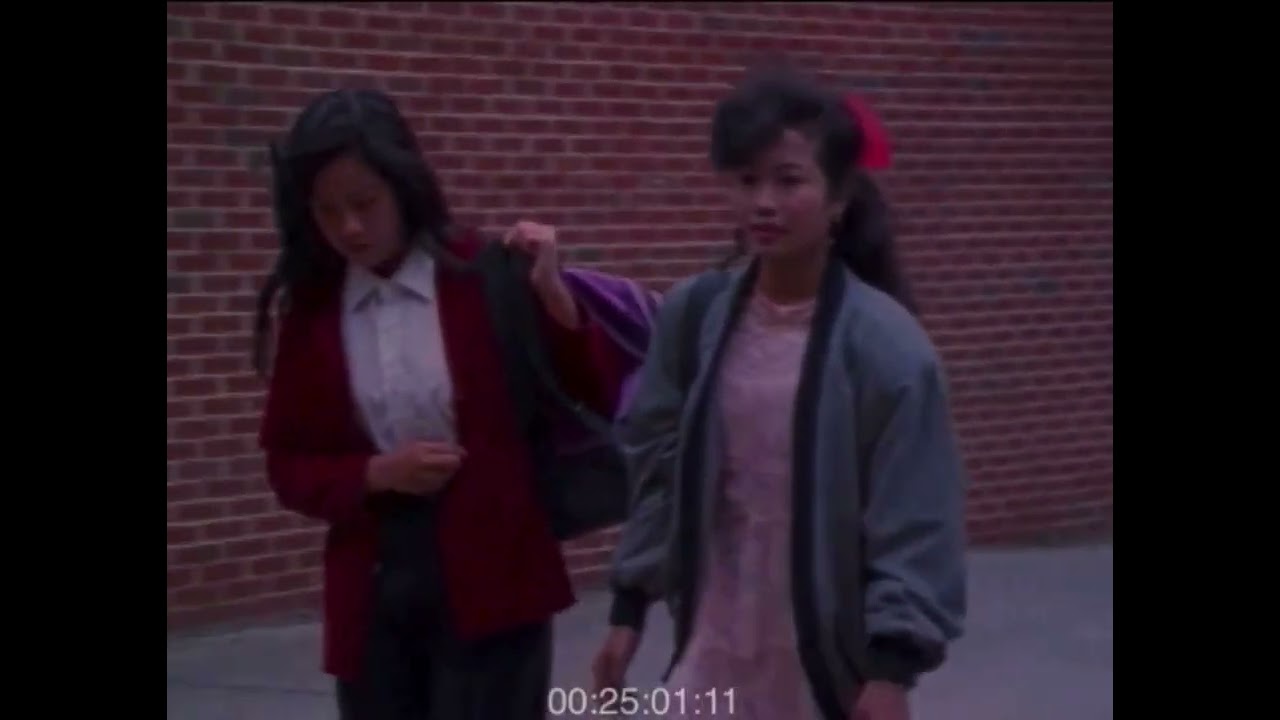

The project started as a photography initiative, carried out by Zeiger and two friends, to document the experiences of Asian and Latinx communities unfolding in apartment complex parking lots, boxing gyms, poultry-processing plants, soccer fields, and other sites. Over time, though, his interests turned to video documentary work—a potential means to capture not just still images of individuals but their voices as well.

While Zeiger’s focus was the everyday lives of his subjects, it was difficult to separate the work from the political climate: Zeiger was filming at a moment when agents from Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) had ramped up enforcement targeting local Latino businesses, construction sites, and factories. (INS ceased to exist in 2003, when federal immigration enforcement was placed under the control of the newly created Department of Homeland Security) Zeiger decided that the best way to understand the local backlash was through film, traveling across metro Atlanta and north Georgia to film communities undergoing massive transformations over the course of two years. The result was a documentary (co-produced with Eric Mofford) offering insight into Georgia’s anti-immigrant politics—but also into the cultural, social, and political worlds migrants were forging in this southern place.

Making Displaced in the New South

“I’m Suttiwan Cox, and I’m an alien.” Early in the film, we are introduced to a woman with a black bob and bangs, standing before an unseen audience. A spotlight shines on her as she smiles genially and the crowd laughs. It’s 1993 in Atlanta, and Suttiwan Cox is performing a stand-up comedy routine. For eight minutes, we listen to her tell anecdotes about her experiences in the United States, featuring her interactions with and observations on the strangeness of American culture. In between her quips and smiles, she tells a true story of immigrating to and settling into life in Georgia during the 1980s.

This past July, sitting on the other side of a grainy video call, Cox reflected on her lifelong career as a teacher and advocate. Immigrating from Thailand, she arrived in DeKalb County in 1977 with her husband, Bruce. In Thailand, Cox had been an English teacher—so, once here, she received a master’s in English from Georgia State University and accepted a position teaching English for Speakers of Other Languages (ESOL) at Cross Key High School.

“I was always teaching,” Cox said recently. During her time as an educator, Cox found prejudice to be the greatest challenge that she and her students faced. “The thing is, if you speak with an accent—with your face what your face looks like—you must be, first of all, stupid,” she said. “One of my students told me she would rather be deaf. You know, that’s a real thing that happened to me in the classroom while I was teaching.” Cox shook her head incredulously. “And that really hit me hard that, man, this kid would rather be deaf.”

The prejudices facing English-language learners extended beyond the classroom. As an education advocate, Cox spoke before lawmakers, news outlets, and community members. However, she was cognizant of the way Americans perceived her due to her accent: “When I open my mouth, they think I’m no one, and they won’t listen.” She began to integrate her comedy routines into her presentations, using humor as a tool with which she could catch the attention and interest of her audience. “I used my stand-up comedy to pull people in to listen,” she said.

“If they can laugh, they will listen and say, Oh, her accent bad. But I understand her . . . And that’s how I go through life as an immigrant and go through life as a teacher for my students.” – Suttiwan Cox, educator and advocate

Displaced in the New South exists due to the willingness of community members to open their doors and lives to a team of strangers. Cox met Zeiger through her husband and quickly agreed to be interviewed; she recalls sitting for hours in the filmmaker’s basement-turned-recording studio, describing her experiences in Atlanta and in the classroom. He also began capturing footage of her stand-up routines, which would serve as a motif throughout Displaced—her performances animate breaks between different portions of the documentary. Throughout the film, stories of building community and finding belonging are interspersed with reminders of the anti-immigrant political climate, as the state sought to push through “English Only” legislation and as cities targeted day laborers through anti-congregation ordinances.

Cox has been highly regarded for her work in Georgia, both as an educator and as an advocate. She knew that these two roles could not be separated, and that shedding light on her students’ experiences was critical in advocating for their rights. When speaking with us three decades later about her decision to participate in the documentary, Cox recalled telling Zeiger, “Do whatever it takes to get their [my students’] story out. Do whatever it takes to get the story out.”

Suttiwan Cox was one of countless individuals featured in Displaced. While she carved out possibilities of belonging through teaching and comedy, others took different routes. Xuan Sutter, for example, worked with the Refugee Women’s Network to help Vietnamese refugees settle into their new homes along Buford Highway. The members of Los Corazones Tristes, a local Mexican band, used their music to bring community members together on the dance floor. The documentary also illustrates how students at Cross Keys High School forged friendships, played soccer, and participated in international celebrations as a means to adapt to a new home.

The exhibit devoted to it Displaced in the New South highlights not just video footage from the documentary, but also photographs that David Zeiger took depicting Asian and Latinx life in the area and ephemera like newspaper clippings from Mundo Hispánico. Still, the exhibit doesn’t dwell in the past; at the Athens exhibit, you can also see art from Buford Highway visual artist and Captura ATL cofounder Victoria García, showcasing some of her contemporary work. García’s images of familial celebrations, vendor stalls with piñatas and watermelons, and shopping centers decorated with signs in Spanish, Vietnamese, and English capture the intertwined worlds of Asian and Latinx everyday life. Juxtaposed with Zeiger’s black-and-white work, García’s colorful photographs testify to the passage of time and the resiliency of local migrant communities.

In September, Suttiwan Cox sat on a panel with old friends—including Zeiger—to celebrate the exhibit’s opening. She reflected on the nativism of the 1990s and shared how she felt about Displaced then and now, saying, “This film helped me believe in humanity.”

Her remarks echoed an earlier conversation, when we asked Cox about her thoughts on the future of Georgia’s immigrant communities. “Oh, I just hope that they don’t live in fear,” she answered immediately. “First and foremost, [that] they do not live in fear. Second, they are not without hope. You cannot—” She paused, taking a deep breath. “You really have nothing left,” she said finally. “Hope is a big word. You keep going because you have hope.”

Iliana Yamileth Rodriguez is Assistant Professor of History at Emory University where she researches and teaches the history of race, labor, and migration in the United States.

Hannah Lo is a junior at Emory University, studying U.S. History with a research interest in immigration and access to rights.