A lifelong love of ice cream, stretching from Palestine to Duluth

Loqman Salem’s new Gwinnett County cafe, Wowbooza, specializes in the chewy, elastic ice cream popular in the Middle East—but rarely found in the U.S.

Loqman Salem had an itch he couldn’t scratch, and it had to do with ice cream.

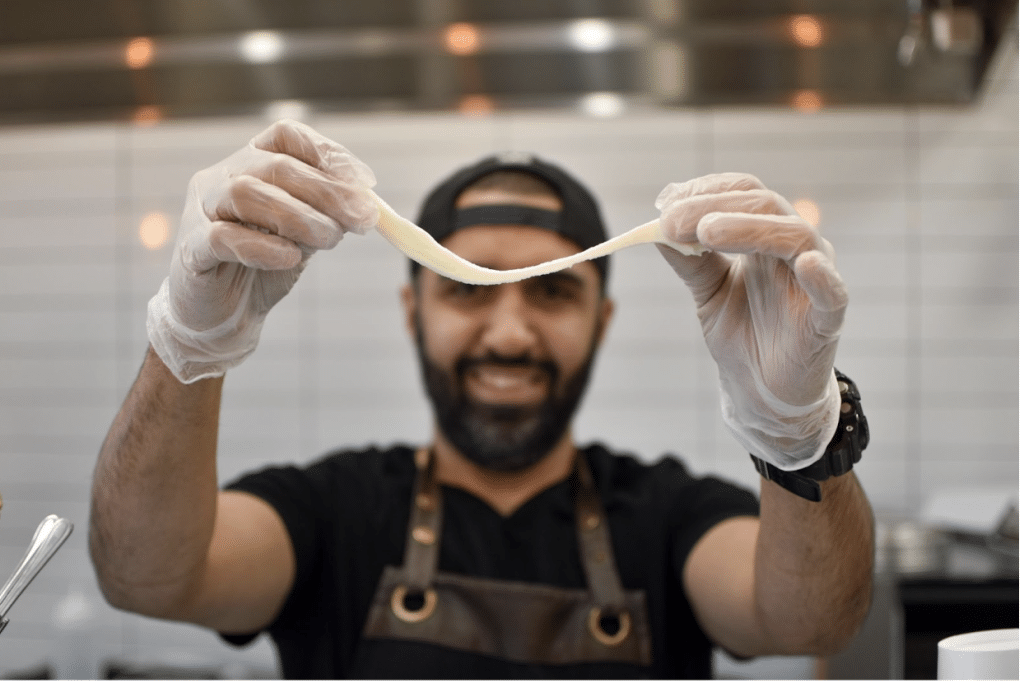

Plenty of people crave ice cream, of course. But Salem had a more specific need—the kind of ice cream served in Ramallah, Palestine, which he remembered from childhood visits with his family. Like Turkish ice cream, Palestinian ice cream is made with mastic, a resin extracted from a tree traditionally grown on the Greek island of Chios. It gives this kind of ice cream—booza in Palestine, Syria, Lebanon, and Jordan, dondurma in Turkey—a distinctive texture. “You chew it like three, four times before it melts,” Salem says. You can hold a piece of it in your hands and stretch it like gum. There aren’t many places in the United States where it’s sold.

Now, one of them is Wowbooza, a brightly lit cafe that Salem opened over the summer in Duluth. Its primary focus is the object of Salem’s obsession—chewy, mastic-based ice cream—but he offers other sweets to go with it: crepes, baklawa, kunafa, and Dubai chocolate bars. Another beloved Middle Eastern dessert, kunafa combines a cheese filling with shredded filo dough (kataifi), and is doused with syrup before being served hot; Salem’s Dubai chocolate bars, filled with kataifi and pistachio paste, were inspired by a viral TikTok phenomenon.

Born in Chicago into a Palestinian family, Salem spent several years as a child in the West Bank, in a small village near Ramallah; his parents wanted him to learn Arabic and experience the culture there. They also wanted him to get a job—so in the summers, Salem became an ice cream salesman, buying product wholesale and retailing it at events like weddings. Ramallah—particularly a world-famous shop called Rukab’s—is renowned for its ice cream, and on his menu today Salem offers a classic Ramallah combination, a single cone with scoops of strawberry, pineapple, chocolate, lemon, and plain mastic, which has a piney flavor.

When he came back from that childhood visit, Salem was bereft: “Here, I never found this ice cream.” His family moved to the Atlanta area and Salem grew up to become a salesman, like his father, hawking products like cologne door to door and at flea markets. But on the side, his childhood love of ice cream bloomed into an infatuation. If nobody here was going to sell it, Salem was going to figure out how to make it.

He read every book he could get his hands on, learning the science behind topics like freezing-point depression and milk pasteurization. Mastic-based ice cream is too thick for many ice cream machines, so Salem developed workarounds, like stacking pans filled with alcohol and dry ice to get the ice cream to freeze properly. (Salem gets his mastic, dried, through a wholesaler.) He spent a lot of money on dry ice, he says: “It’s like somebody gambling—and it was not for business! I was making ice cream just to get that taste.”

Finally, he found a machine that would work for him; he purchased a pasteurizer. “I started buying a lot and putting it in my house. I had one room just for equipment,” says Salem, who lives in Lawrenceville with his wife and three children. “My father was like, ‘Why are you making so much ice cream? Your cholesterol’s gonna go high.’ And I was like, ‘You’ll see—this ice cream’s gonna become something.’”

One day, a man was buying bread from Salem’s mother—she bakes Palestinian bread in a homemade oven in Lawrenceville, selling it to family and friends—and Salem offered him a sample of his ice cream. The man declined: He thought it was just American-style booza, nothing special. “I was like, ‘No, this is booza booza,’” Salem recalls. The man relented—then, having tasted it, swiftly asked for more ice cream to give to his daughters. He also connected Salem with the Alif Institute, a nonprofit Arab American cultural center, and Salem soon started selling ice cream at Alif-affiliated bazaars and other festivals around town, building up to the launch of the new brick-and-mortar.

Wowbooza is already popular, open till midnight on weekends and drawing in crowds from all over the place. Located in a shopping plaza off Pleasant Hill Road, the cafe is in the middle of a diverse area with big Korean and Vietnamese populations, as well as the people of Middle Eastern descent who stop by in search of familiar flavors: “People come here, like, not even thinking that they’re gonna eat the ice cream that they eat back home,” Salem says. He shows off the premises with the enthusiasm of a proud parent, pointing to the prep room, stocked with Belgian chocolate, pistachio paste, and saffron and other spices; pots for serving mint and sage teas and cardamom-spiced Arabic coffee; and a display case filled with a variety of ice creams.

And a special stovetop, imported from Turkey, for kunafa—it rotates the pans over a flame. Salem makes a softer kunafa in the style of the West Bank city of Nablus, plus a crunchier Turkish kunafa. Preparing the latter version one recent afternoon, he carefully flipped the pastry so it’d brown evenly on both sides, then served it sizzling hot—the cheese inside of it gooey and rich, the long strands of kataifi like crisp noodles, a sprinkle of pistachios on top. The dessert is meant for two people and can be ordered a la mode.

Everything is from scratch: Most parlors purchase an ice cream base and flavor it but, Salem notes, his is homemade. Then he adds flavors like saffron-cardamom, Arabic coffee, Biscoff, pistachio—and one called Crazy Oreo. “I call it Crazy Oreo,” he says, “because it’s Oreo . . . but it’s stretchy.”