An effort to capture Asian American community stories in Georgia, one phone directory at a time

“History wouldn’t be complete without this voice” – Georgia Asian American Community Archive Initiative on mission to enrich Southern histories

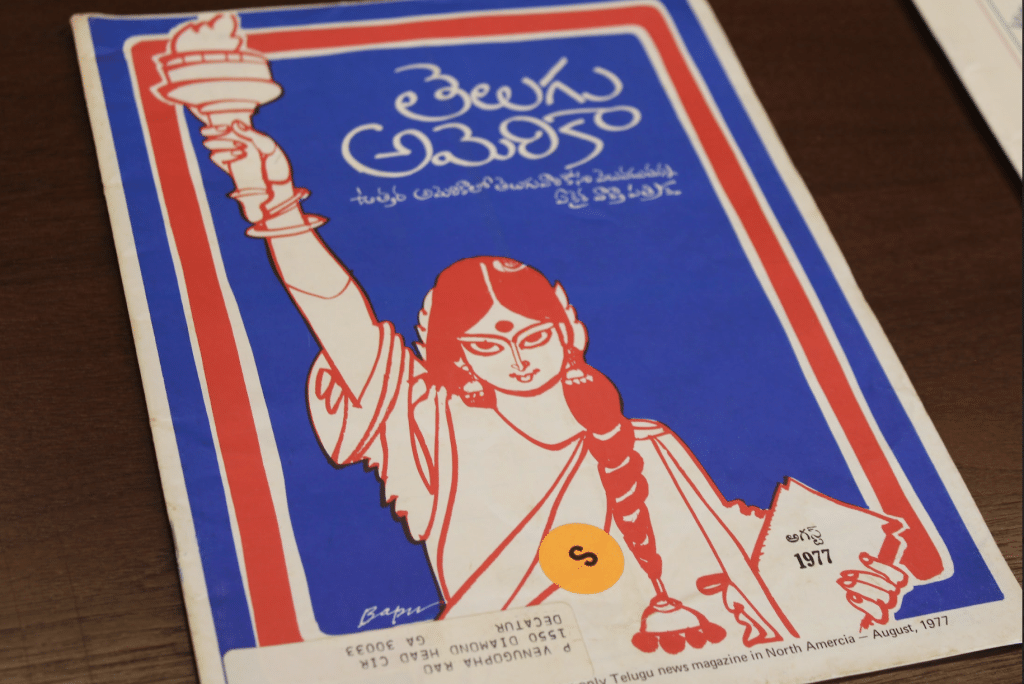

Two years ago, Gautham Reddy got a call from Mrs. Rao, a Telugu-speaking auntie in DeKalb County. She asked him to come over and see a collection of books – hundreds, in all – left behind by her late husband, Dr. Pemmaraju Venugopala Rao, a physicist at Emory University who had died in 2012. “[She] basically said, we have built up this large personal library of Telugu material over his life.”

Mrs. Rao had gotten in touch with the right person: Gautham is Emory’s South Asian Studies librarian, and one of his goals is to bring more diversity to the university’s South Asia collections. He has expertise in multiple South Asian languages, including Sanskrit and Hindi, but grew up speaking Telugu, a language spoken in parts of southern India. Gautham lived briefly in the metro Atlanta area as a child, before his family moved to Minnesota, where he helped document stories of the South Asians who migrated there prior to 1965 for the South Asian American Digital Archive. “I just found that early history of immigration so fascinating,” he said. When he moved back to Atlanta as an adult, he was surprised to see there wasn’t a sustained effort to capture Asian histories. “I kind of assumed that there would already be some kind of ongoing effort that I plug into, and I realized that there wasn’t.”

When he walked into Mrs. Rao’s basement, he found books, stacked “every inch” from floor to ceiling, that had been amassed over fifty years. In 1959, when the Raos moved to the U.S. from India, books in South Asian languages weren’t easy to find, Gautham explained, so “they just built their own community library.” He took several hundred, he said, including rare and out of print copies, to add to Emory’s collections.

But thumbing through the piles of books and documents, he discovered something else: they were among the first people in Atlanta to establish a community organization for Indians.

The Raos were among a small handful of Indian families in the Metro Atlanta area who immigrated here a few years before 1965, when the Immigration and Nationality Act removed national origin quotas, ushering in a wave of people from Asian countries. In the last twenty years alone, the Asian population in Georgia has nearly doubled, with most of that growth concentrated in the Atlanta metro area, and with Indian-Americans being the largest group. With that growth has come not only a proliferation of everything from South Asian grocery stores and restaurants to temples and mosques, but also, community organizations.

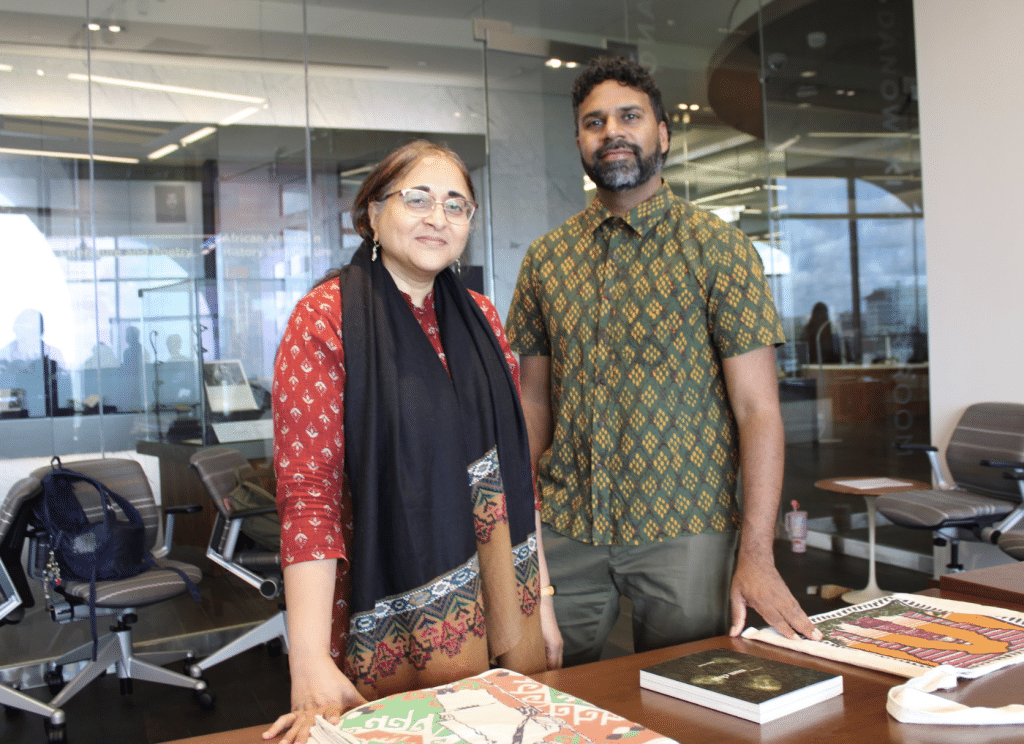

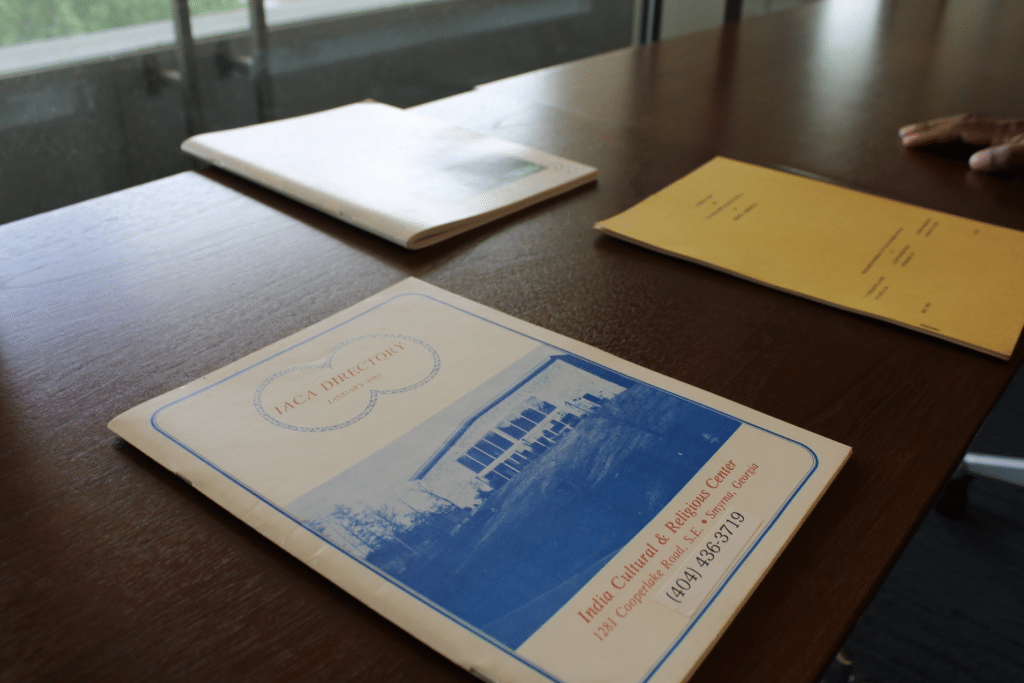

In Atlanta, the Raos were “one of the founders of the Indian American Cultural Association,” one of the first of those community organizations, said Gautham, standing in the Danowski Seminar Room of the Rose Library – Emory’s repository for archives, manuscripts, and rare books.

He held an IACA directory, dated 1987, listing dozens of Indian households, complete with their addresses and phone numbers, with an additional page at the end where numbers and names have been written in. “They preserved a lot of the initial organizing documents,” of the IACA. They also had, he said, “colorful parts of sets from stage plays put on at the Indian American Cultural Association,” as well as “calendar art from local South Asian businesses” and flyers from past cultural events.

“That’s a lot of the kind of material that just disappears.”

In “library world,” he explained, maintaining a South Asia collection is understood as focusing “on anything from or about South Asia, and it’s over there another side of the world.” The transnational element of being South Asian isn’t always reflected. “South Asian diasporas are a big part of shaping how we think about South Asia,” he said. “I mean, just look at the impact of, for one example, the Indian diaspora on Indian politics, right?” (Indians in the diaspora have organized to give millions of dollars to political campaigns; in the U.S., for example, there were reportedly 10,000 volunteers working with Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s party, the BJP, in the last election.)

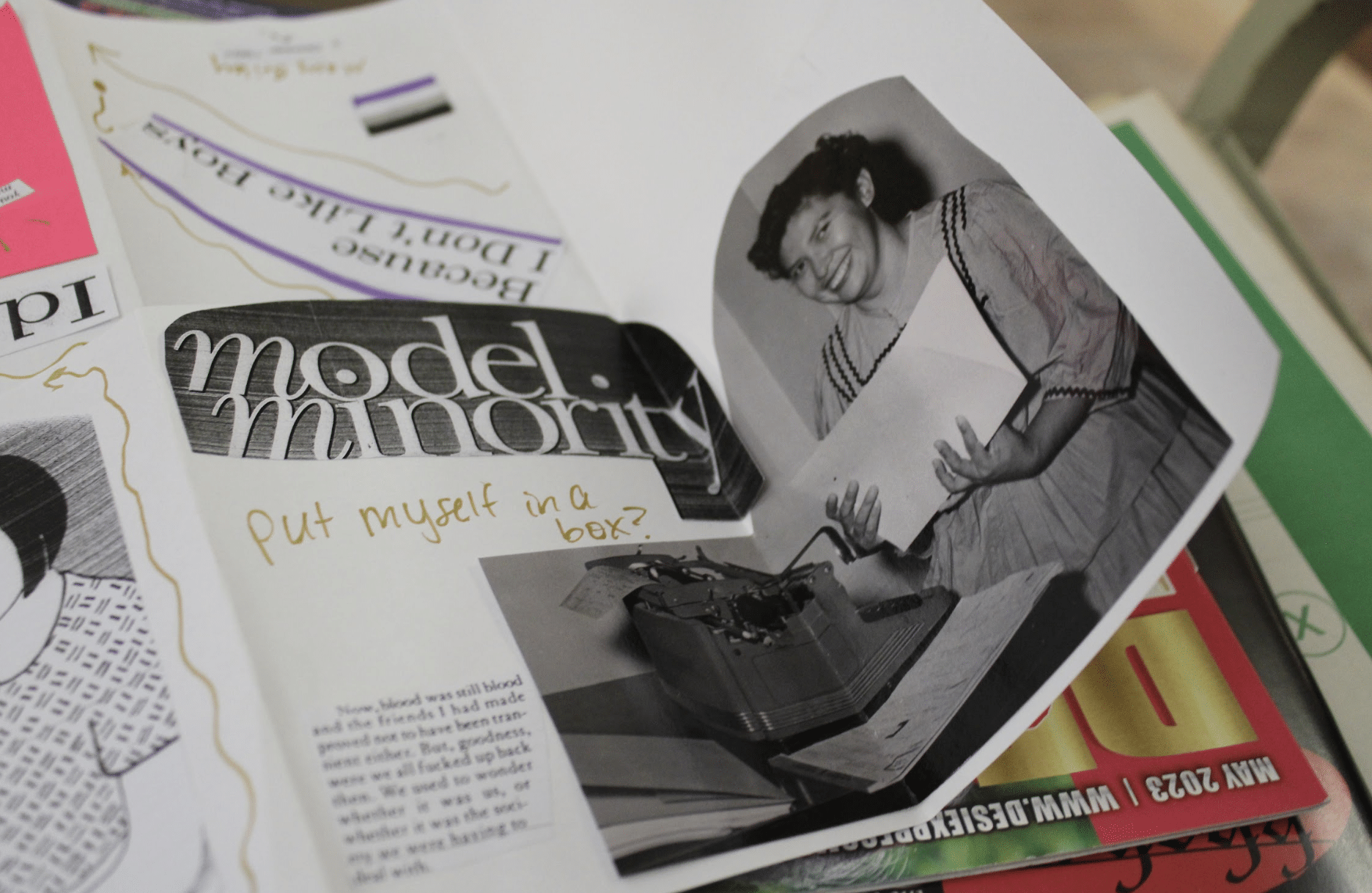

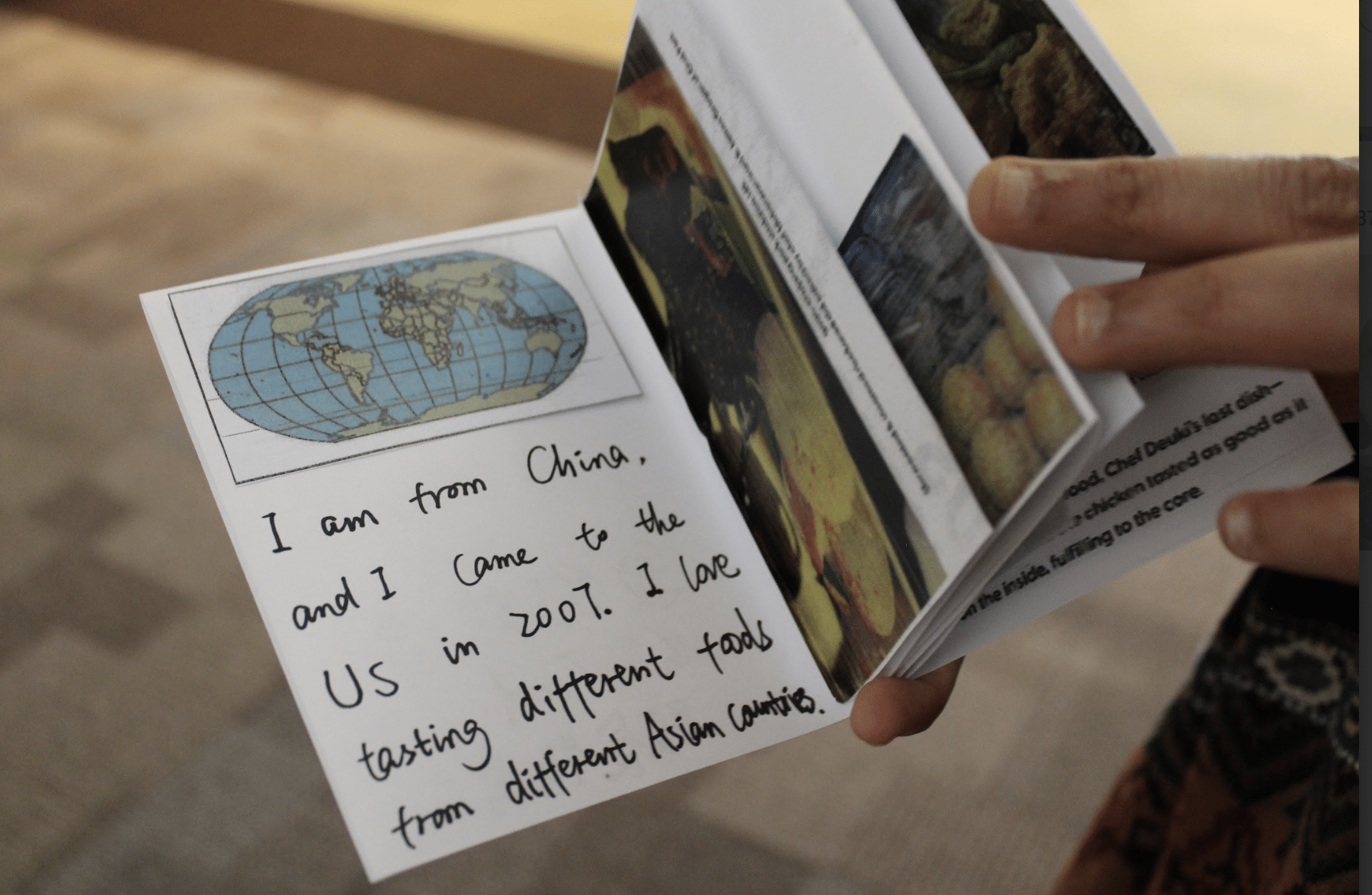

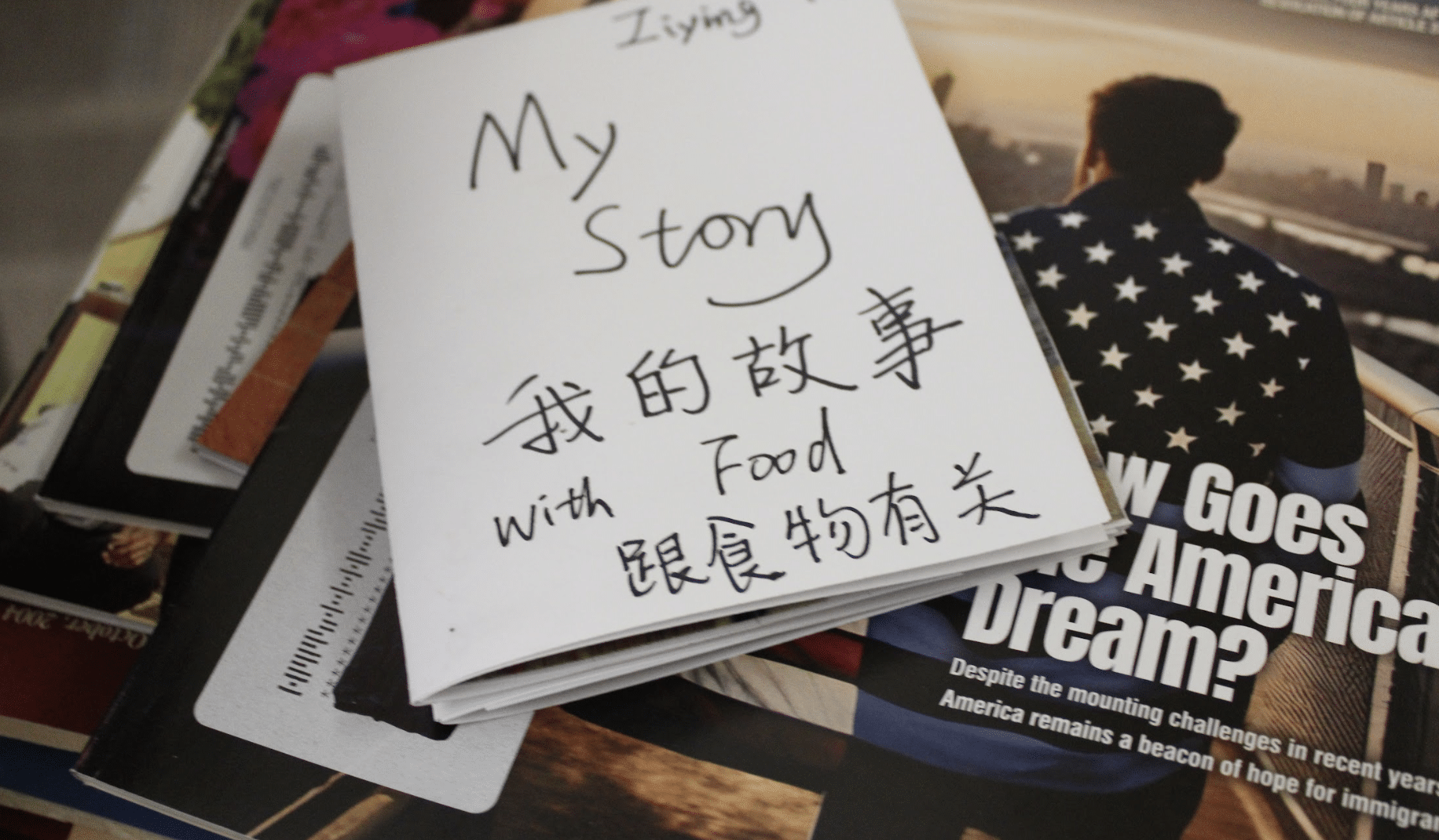

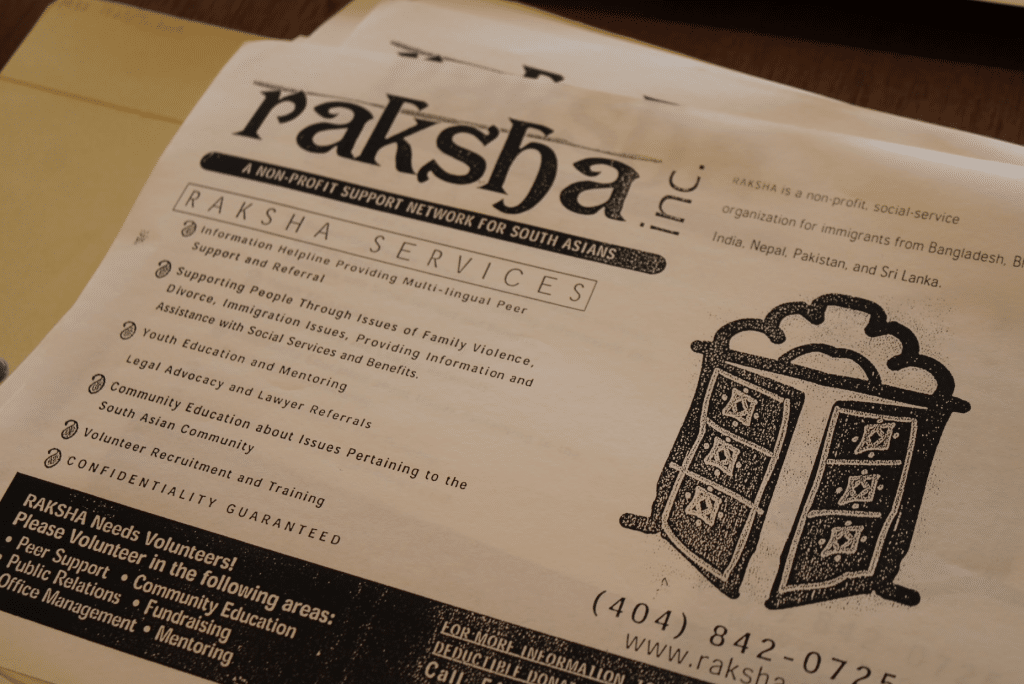

Since those discoveries in the Rao’s basement, Gautham and another Emory librarian, Chella Vaidyanathan, have embarked on an ambitious project: the Georgia Asian American Community Archive Initiative (GAACAI). Their goal is to not only gather old documents to archive, but to build awareness of Asian American histories in the state and also to help develop an infrastructure to support Asian American storytelling. That means eventually bringing some of the stories to places like the Atlanta History Center, which to date, has not widely documented Asian immigrant histories, helping people in the community archive their stories, and working with existing community groups who are already archiving their stories (they recently hosted a panel with a speaker from We Love Buford Highway, Inc, which works to preserve the histories of immigrants in the corridor). GAACAI already held two zine workshops, where community members – some driving from as far as Athens – are challenged to dig deep into their own histories, and create booklets (zines) telling their own stories.

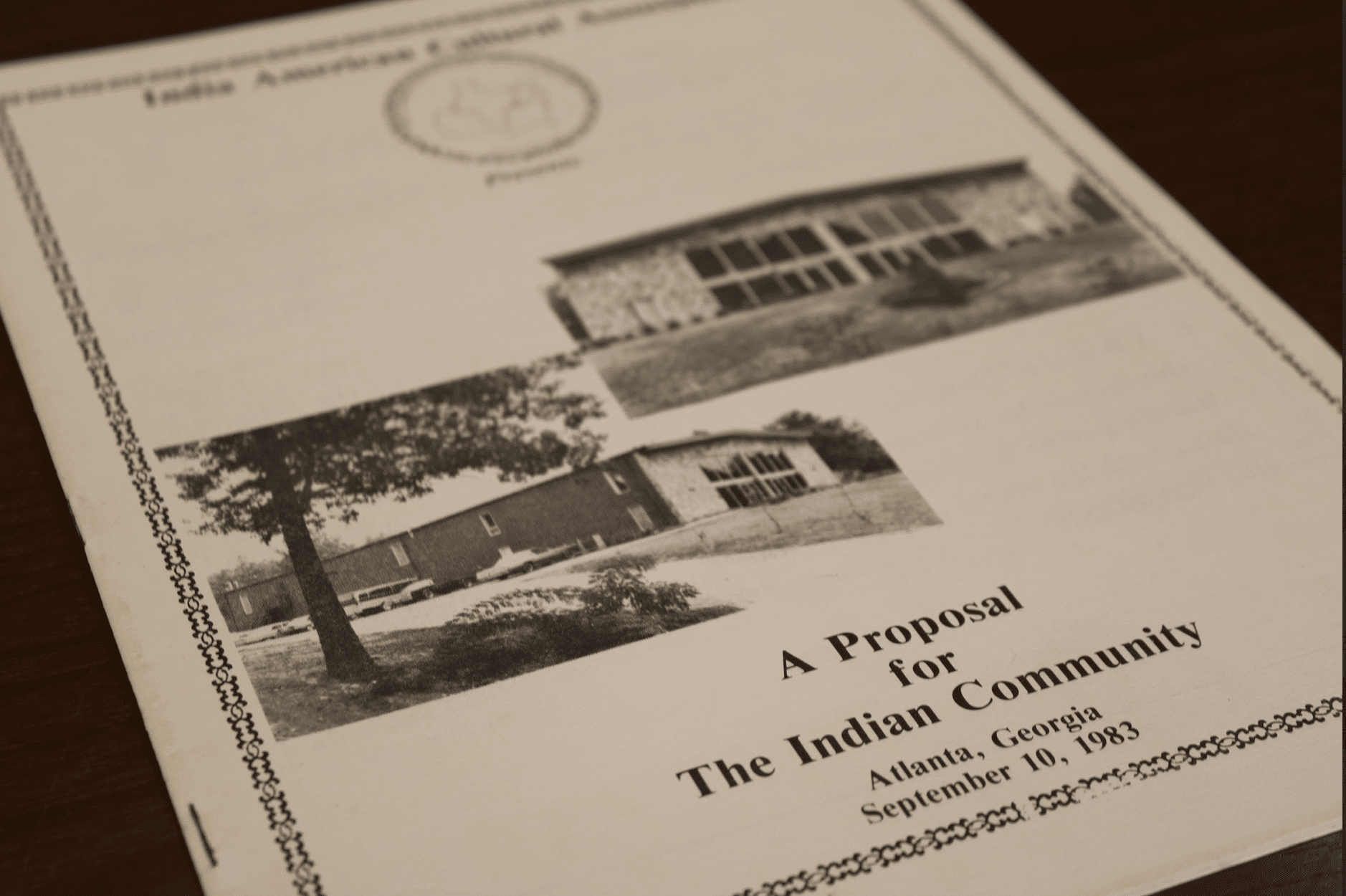

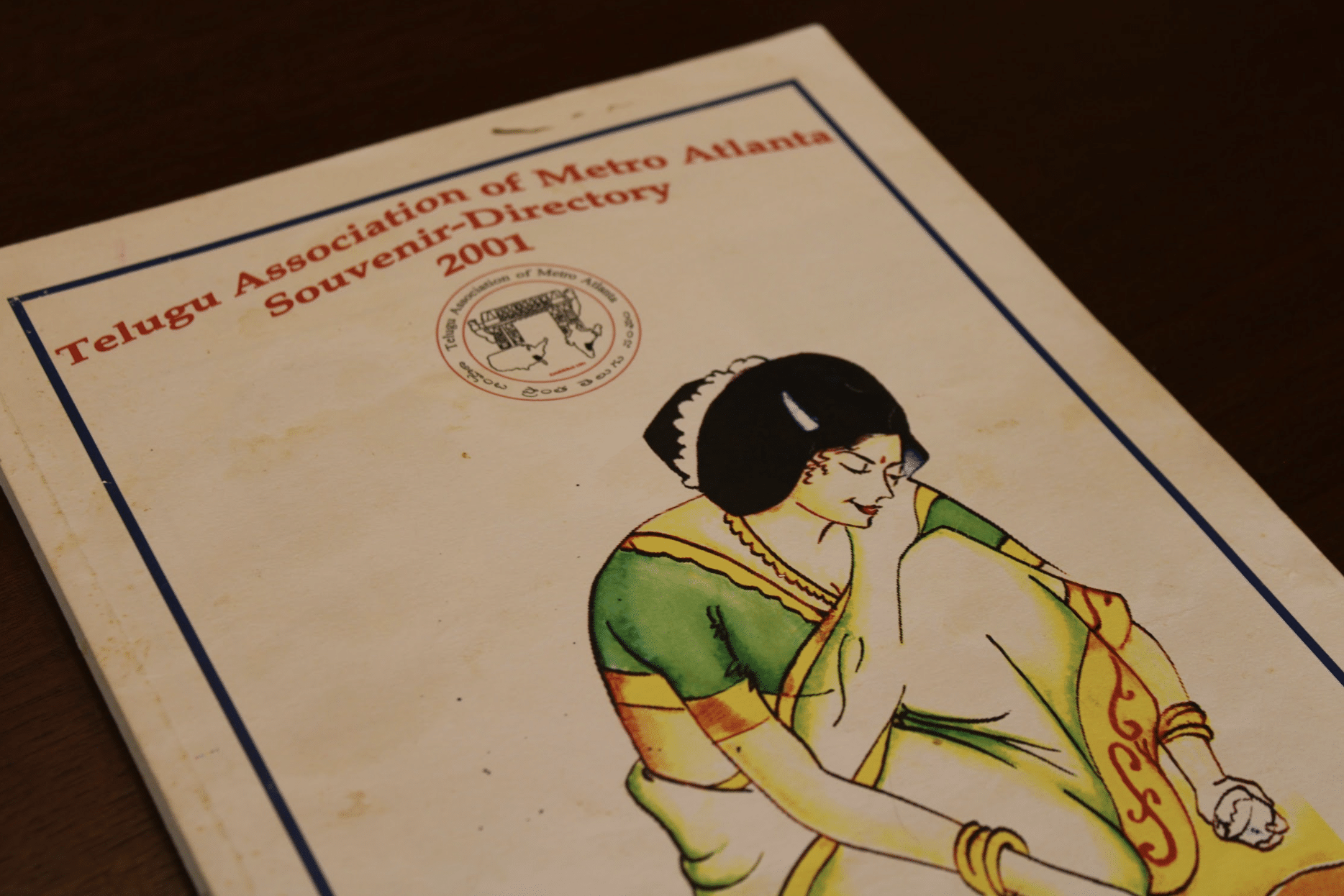

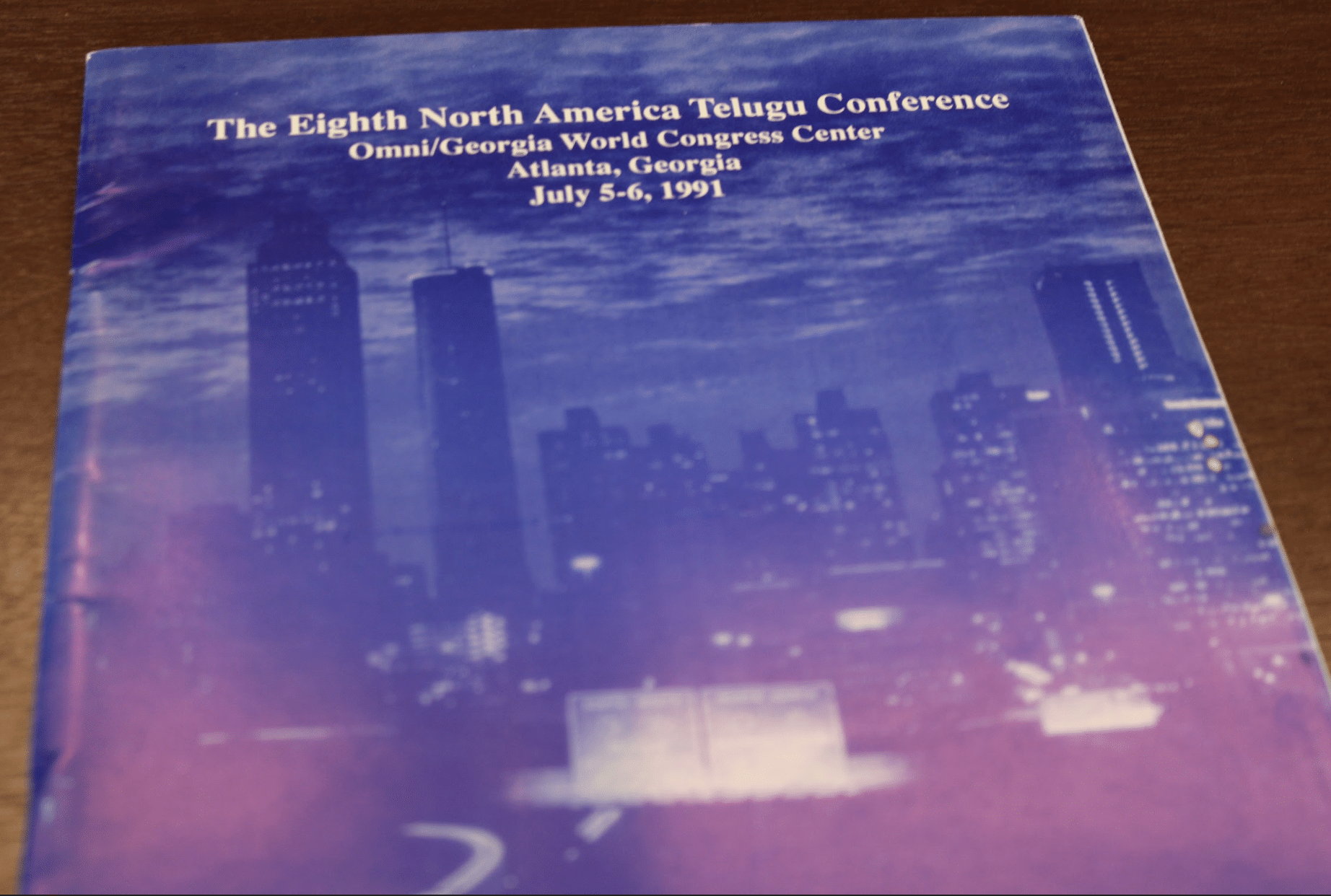

At the Rose Library in June, Gautham and Chella had carefully laid out some of what they’ve archived so far: Along with phone directories from the IACA as well the Telugu Association of Metro Atlanta directory, there’s a 1983 proposal for an Indian community center, and program booklets from the annual Festival of India.

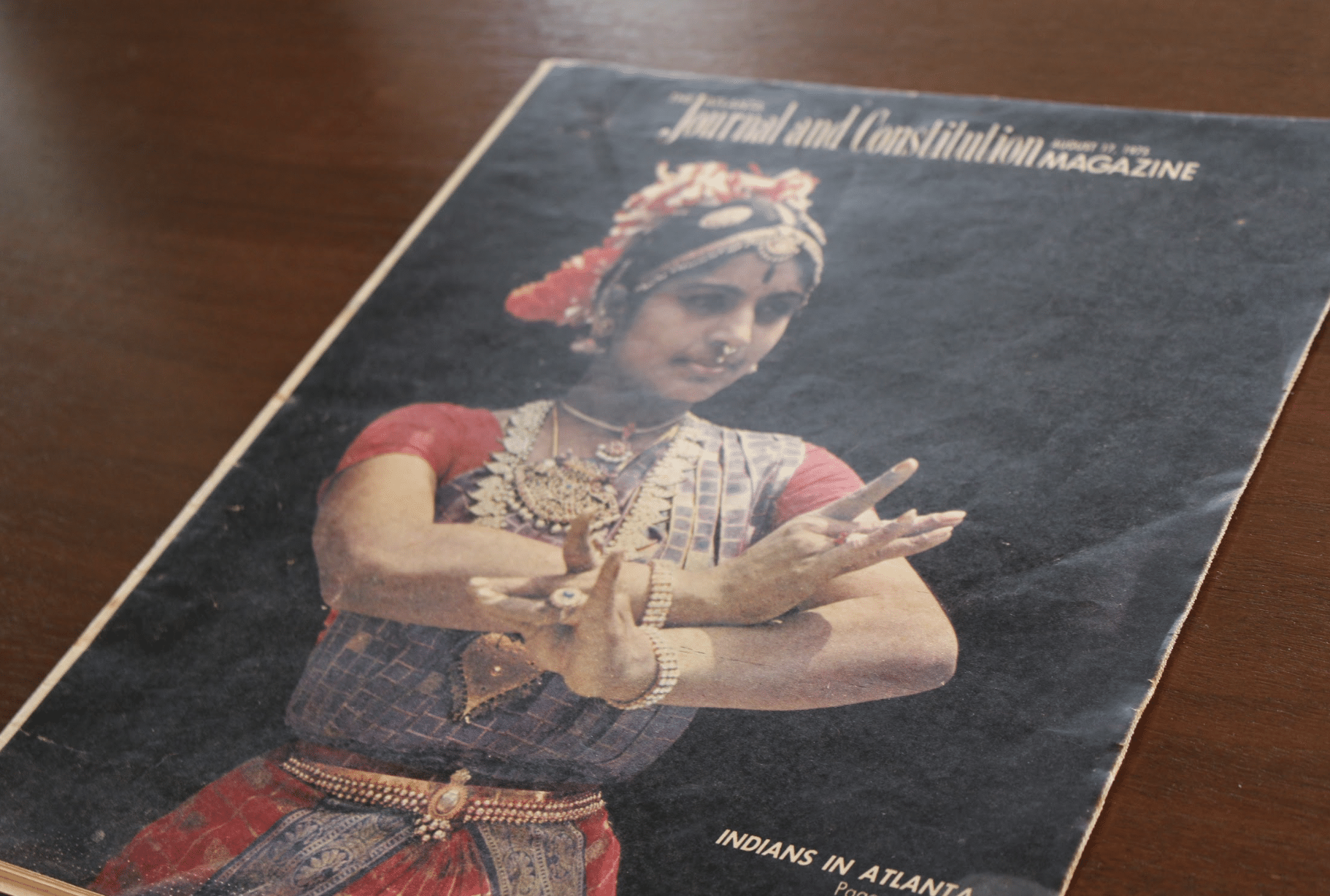

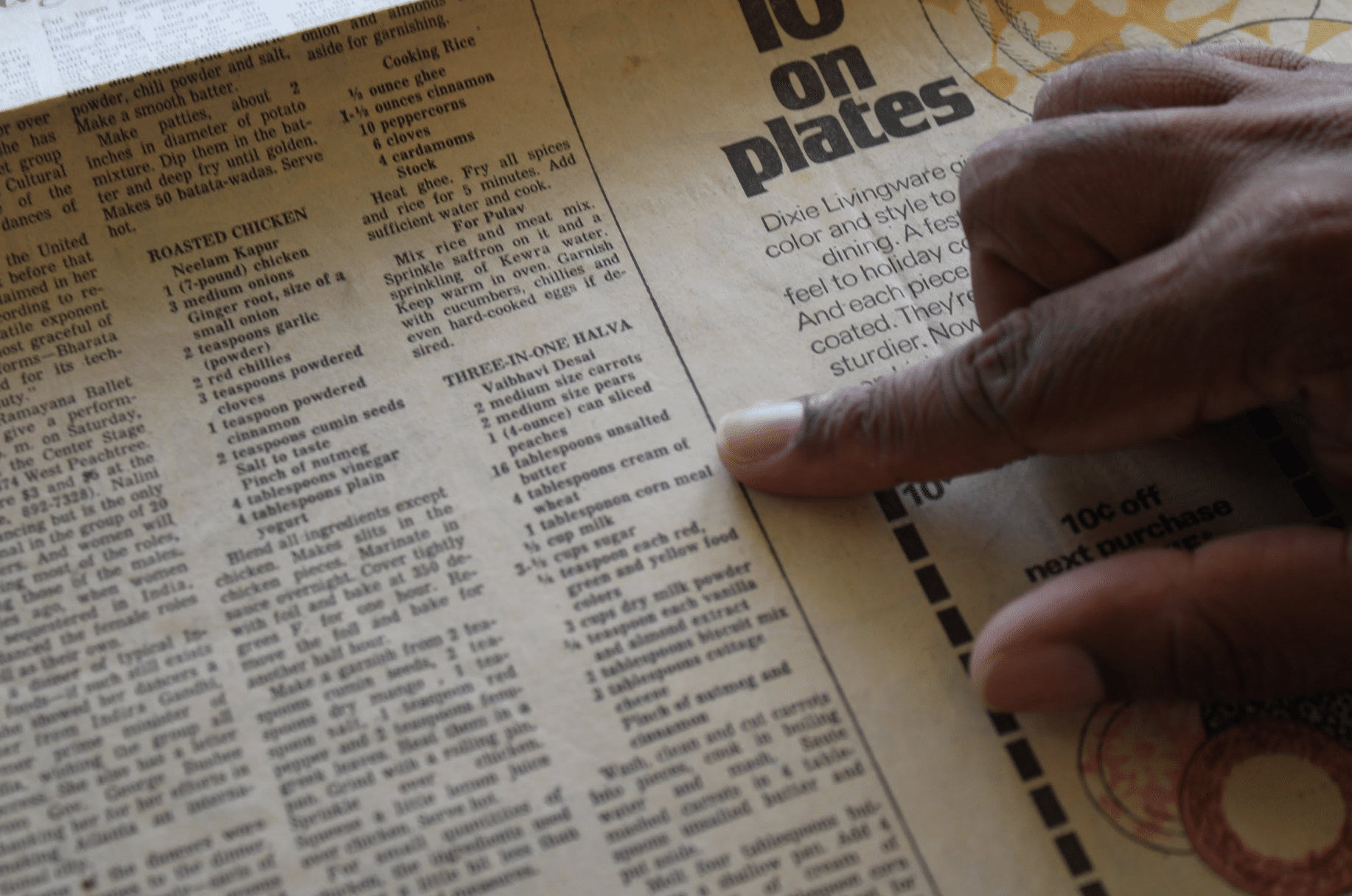

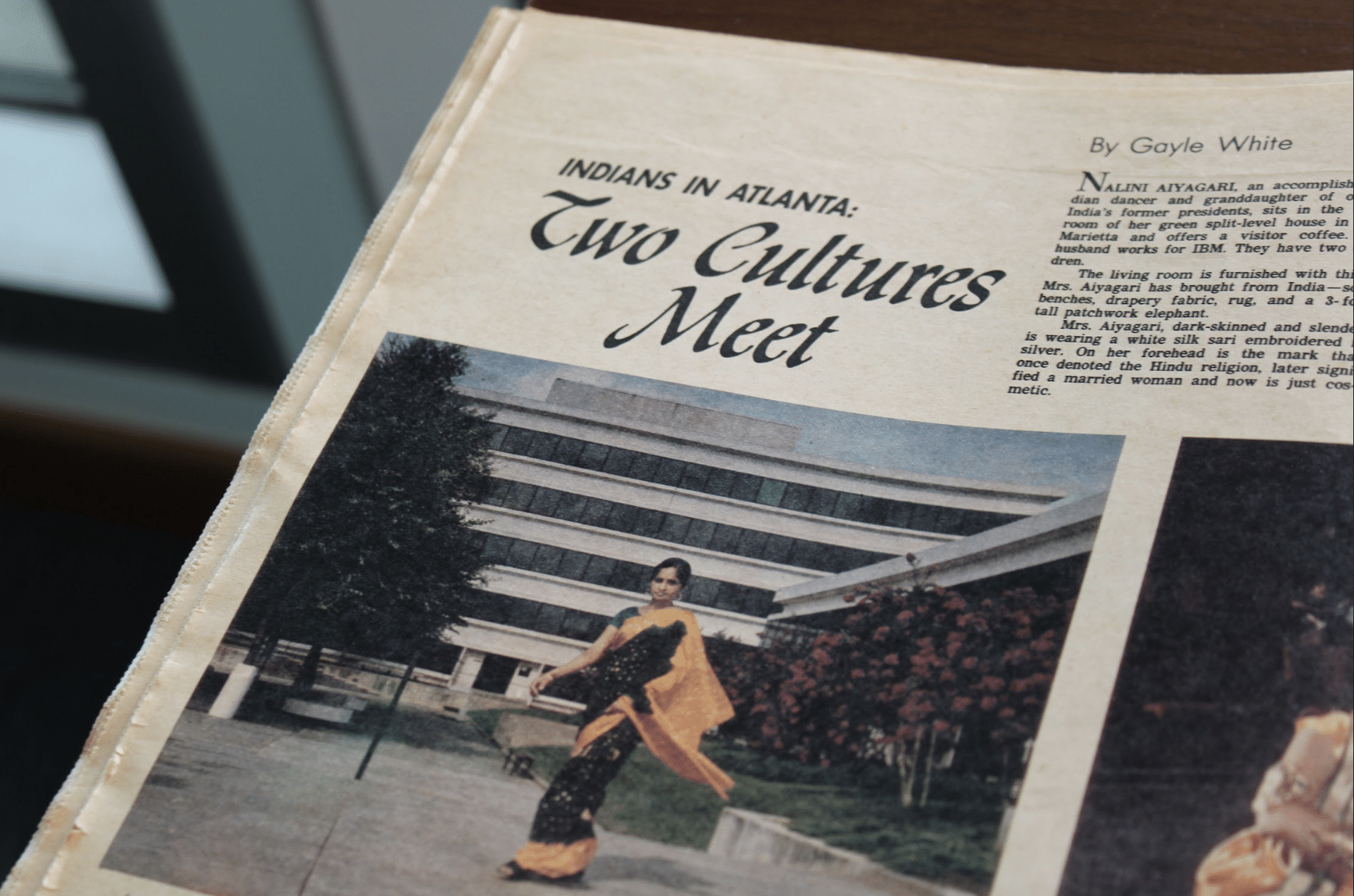

Gautham and Chella are also collecting community media—they have stacks of Khabar magazine, including the first-ever edition—and even have clippings from the first time the Atlanta Journal-Constitution ran a big cover story on Indian Americans, in 1975. Gautham pointed to one section of the article listing the ingredients you can buy from an American grocery store to make halva. “If you look at the ingredients that are in this halva, there’s canned peaches, cornmeal, and cottage cheese.”

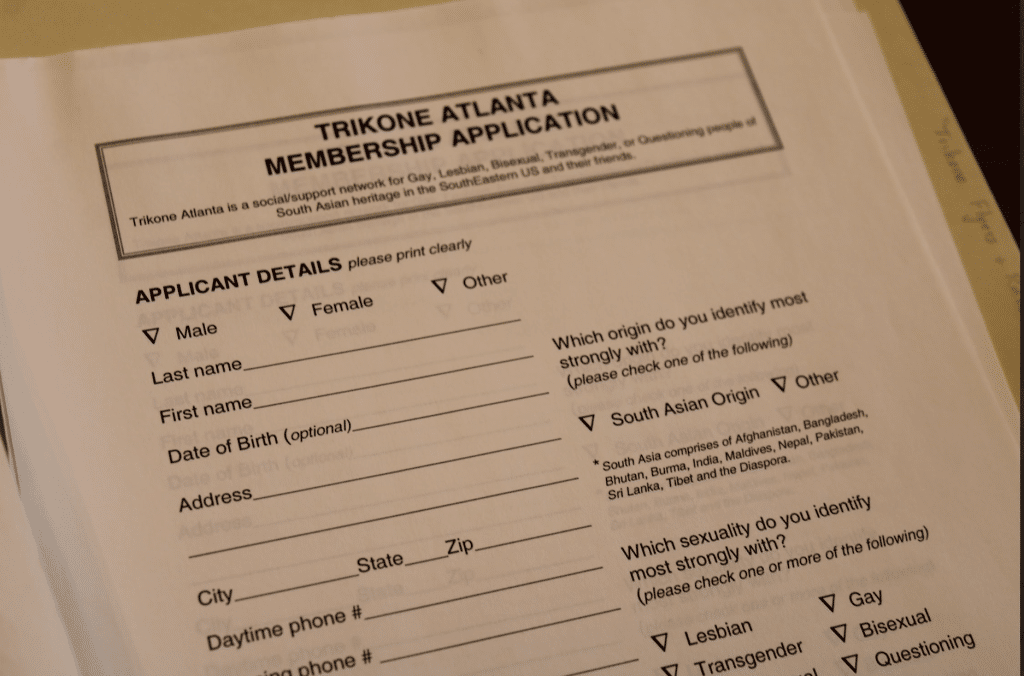

Another part of the archive, said Gautham, walking over to stacks of papers and newsletters, is the Trikone collection. Atlanta was home to one of the first chapters of Trikone—an organization for South Asians who identified as LGBTQ. “Atlanta, of course, is a big hub for LGBT activism, and it’s called the gay capital of the South,” he said. “And so there’s this neat intersection, because it’s also a big hub for Asian American communities.”

Those documents were donated by a local Trikone member, and include membership forms as well as newsletters from chapters around the country. “I kind of think of that as like an interesting parallel with the Rao papers, because the Rao papers are very much focused on, kind of, mainstream. They’re very family-oriented,” Gautham said. The Trikone materials, on the other hand, are “very radical queer left,” but, he added, “the challenges they faced are kind of different, also overlapping.”

GAACAI is still in its infant stages. In the coming months and years, Gautham and Chella hope to continue to build out the collections by forging connections with local communities. “It’s very South Asia–heavy right now, because of who we are,” said Gautham. They’re constantly looking for ways to expand; right now, for instance, they’re working with a Korean-speaking graduate student and just finished a review of Korean American publications in the Atlanta area.

“If you know East Asian American communities, Southeast Asian American communities, who have collections of these magazines or periodicals or other artifacts, or other kinds of collections, photographs—I mean, you name it—it would be great if they could get in touch with us,” Chella said. [You can get in touch with organization here].

Involving more community members in the storytelling process is key, said Gautham. At community storytelling workshops, he said, oftentimes elders don’t realize their stories are something that can be archived—that make up the fabric of Georgia, of the U.S.

“I’ve been talking with so many people that came in the ’60s and ’70s. So they’re much older, they have grandkids,” Gautham said. “But people are always interested when we actually tell them what we’re doing and they realize: Oh, this could be history.”

GAACAI will have a booth at the upcoming Festival of India in Atlanta in August. They also plan to organize another zine workshop in October. Stay updated here.