At Aki Mart in Lilburn, Ethiopian food meets Ethiopian fashion

Zelalum Alemayehu dreamed of having a clothing boutique, but also wanted to open a grocery store. She decided: Why not both?

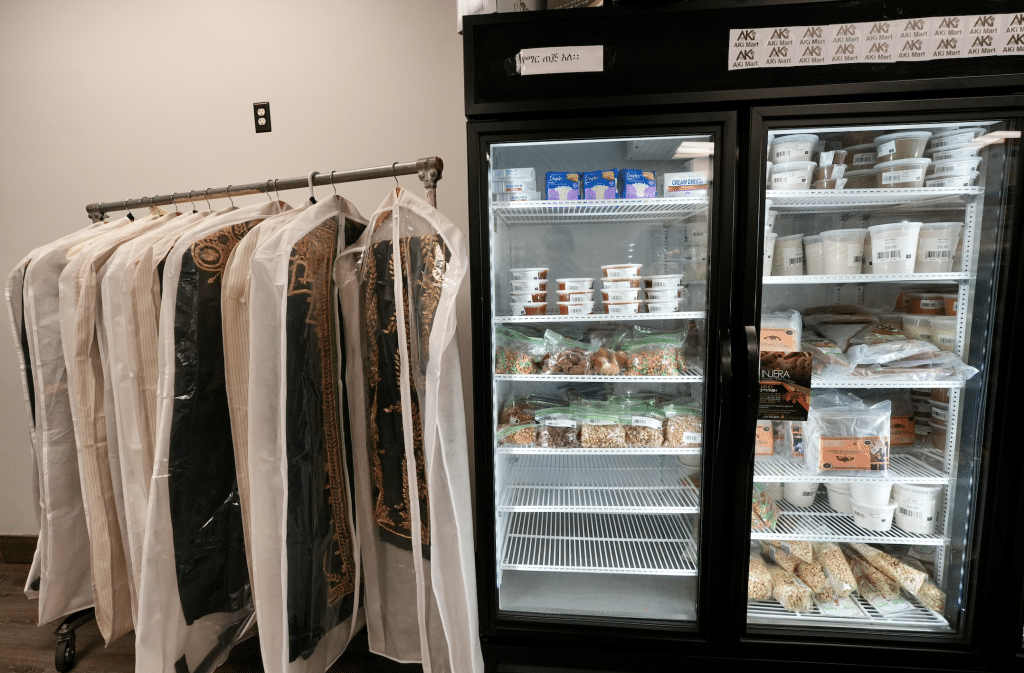

Zelalum Alemayehu’s dream was always to open a fashion boutique. But a food business had the potential to provide a more reliable income. So last fall, she did both: Alemayehu and her husband opened a combination clothing store and food shop in a small strip mall on Killian Hill Road in Lilburn. At Aki Mart, customers on their way to look at colorful, floor-length habesha kemis dresses pass neat shelves bearing plastic tubs of Ethiopian spices, piles of the fermented flatbread injera, and traditional cookware and sundry items—horse mane whisks for religious ceremonies, books from local Ethiopian-American authors, jewelry, and pottery.

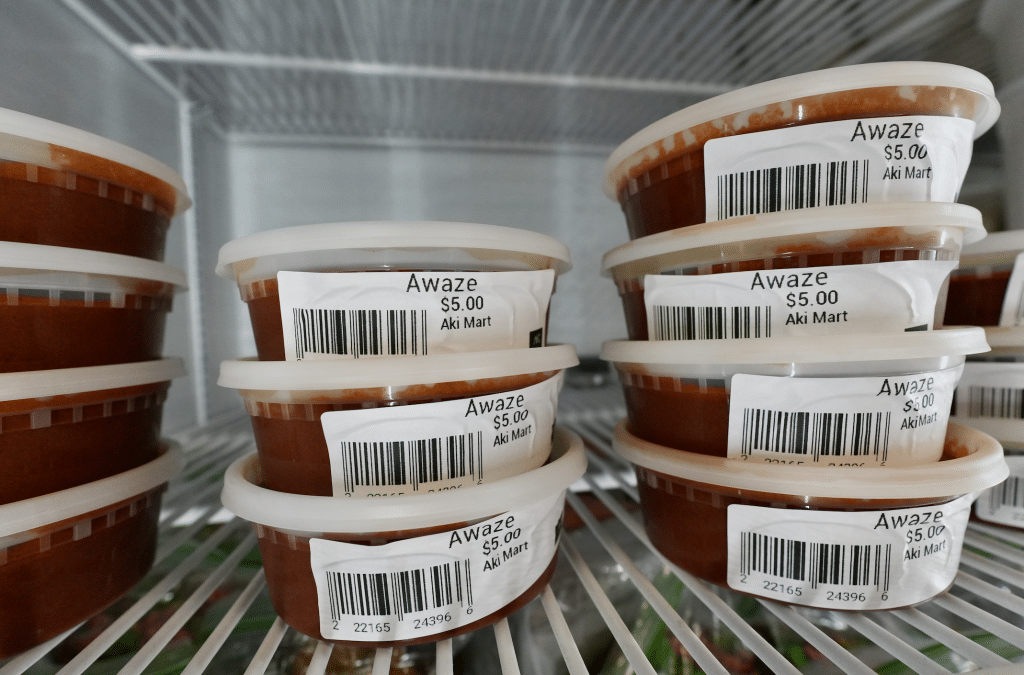

In addition to groceries, Alemayehu prepares fresh food and drinks at home to sell at Aki Mart: not just injera but lentil-filled sambusa pastries, an Ethiopian-style funnel cake called mushabek, and bottles of the bright-orange honey wine tej.

It’s a shop with broad appeal for Metro Atlanta’s burgeoning Ethiopian American community. One customer, Menge Gizachew, says his wife has her dresses altered here while he comes almost every day for injera—which Alemayehu prepares without preservatives. “They use pure teff flour,” Gizachew says. “Other stores mix something in their injera.”

Alemayehu brings more than two decades of food and fashion experience to Aki Mart. Born in the Ethiopian capital, Addis Ababa, she worked at a young age as a tailor in her father’s clothing store. Her mother also worked in the shop, and inspired Alemayehu’s fashion dreams. “My mom has a diploma in alteration,” Alemayehu says. “She dressed up me and my siblings when we would go to school. When I grew older, she taught me how to use a sewing machine.”

In 2005, she moved to Metro Atlanta, joining an Ethiopian community that’s continued to grow in recent years: Between 2012 and 2022, according to the U.S. Census, the number of Georgia residents who identify as Ethiopian nearly doubled from 11,890 to 23,384. For the first 13 years she was here, Alemayehu worked at several Subway restaurants in DeKalb County. That’s where she learned the value of customer service, she says: “It’s not only about smiling and satisfaction—it’s also about having a good smell and temperature. And when a customer asks for something and I don’t have it, I immediately bring it the next day.”

While working at Subway, Alemayehu launched a clothing business out of her home. Now, at Aki Mart, she wears a tape measure around her neck: In between customers, she’s often working on outfits in the back, hemming and altering Ethiopian dresses. In one corner of the store, intricate gold patterns on thick royal blue and dark red velvet Ethiopian suits peek out from under white garment bags. She rents them for weddings: $150 for three nights.

“She is really good at alterations,” says another customer, Zee, who ducks into the restroom to try on a white sleeveless silk dress. She emerges with a smile—it’s a perfect fit.

Alemayehu gets some of her merchandise wholesale, but she largely relies on a more informal network: acquaintances—everyone from airline hostesses to family members—who bring clothing and food items in their suitcases from Ethiopia. She says a majority of her customers are of Ethiopian ancestry, but about a third are South American, South Asian, or white.

She credits the diverse clientele to her store’s layout: It’s spotless. The aisles are organized logically, with similar items grouped together. She says she’s always been put off by cramped Ethiopian stores where the clothing selection is small to nonexistent.

“When I used to go into the stores in Clarkston, I was thinking, How am I going to fix it?” Alemayehu says. She also makes sure that food scents are contained: “When you go to other stores, you can smell people cooking in the back,” she says. “I want no smell. It could contaminate the clothing.”

Aki Mart accepts SNAP and EBT for lower-income shoppers and helps immigrants stay connected to their families. Customers bring cash to send remittances to Ethiopia or load up their phones with international calling credits.

The store made it through its first year, but Alemayehu says she hopes to do well enough to hire another employee to help her. Today her husband, Aschalew Bezabih, pitches in whenever he’s not working as an IT professional—which helps cover the store’s rent. For now, she said, she is counting her blessings.

“This is my dream. I made dresses, so it’s my creativity showing through the store with all the dresses,” Alemayehu says. “If I have something in mind, I do it. I have confidence and I believe in God. This is from God.”