Alongside The Presidential Race, A Referendum To Increase Atlanta Area Transport

Immigrant communities say it’s time for better public transportation, to serve them, and others.

This story was published with support from the election reporting fellowship at The Pivot Fund, a venture philanthropy organization empowering independent BIPOC-led community news.

Brian Ramirez grew up in a family without a car in Gwinnett County, an Atlanta suburb where it can be exceedingly hard to get around without one. Speaking at a forum sponsored by the Asian American Advocacy Fund, he told the gathering about the difficulties his family had faced. “One thing that was consistent throughout my childhood was that transportation was an obstacle.”

Ramirez was born in Colombia and came to the Atlanta area as a child with his parents, who worked long hours and sometimes held down multiple jobs. With limited access to buses, they often relied on taxis, which meant spending money “we really didn’t have,” Ramirez said. “Reliable affordable transit could change everything for them.”

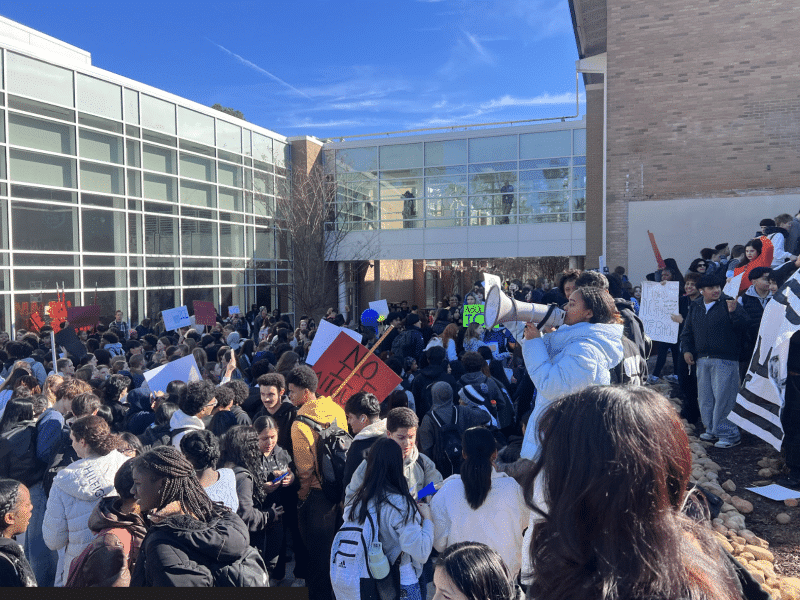

The Asian American Advocacy Fund, a progressive political organization for Asian Americans in Georgia, had convened the event to help spread awareness of two ballot initiatives that would expand transit infrastructure in Gwinnett and Cobb counties, whose immigrant communities have grown rapidly in recent decades. (Materials promoting the event were available in Korean, Chinese, Spanish, and English.)

Alongside casting a ballot in the U.S. Presidential race, voters in both counties will also be able to vote to fund (or deny) an expansion of public transit funded through a special-purpose local options sales tax, or SPLOST. If it is successful, the 1 percent tax would fund up to 75 transit projects in Gwinnett over 30 years, including an expansion of bus services, a direct new route to Hartsfield-Jackson airport, and microtransit—a kind of publicly operated rideshare service. Cobb County is looking to fund projects including six new rapid transit routes where buses would have their own designated lanes; in other words, they don’t get stuck in Atlanta traffic.

Groups like AAAF say public transit could be a lifeline for immigrant families like Ramirez’s, many of whom lack options for getting to work, the grocery store, or the doctor’s office. Another speaker at the event, Shera Sarwar, detailed the routine difficulty she experiences traveling between classes at Georgia State University and her home in Gwinnett. “This situation isn’t just unique to me,” she said. “Many people who depend on public transit face similar hurdles.”

Expanded public transit could also be especially impactful for newly arriving refugees and immigrants, who face many obstacles in getting on the road. And, it would impact undocumented residents in the counties (in Gwinnett alone, there are nearly 80,000 undocumented residents, and in Cobb County around 40,000, according to a 2019 estimate from the Migration Policy Institute), who are banned by state law from getting drivers’ licenses in Georgia, and have to rely on carpooling, taxis, or driving at the risk of getting pulled over and arrested.

If the Gwinnett referendum passes, it will be the first large-scale successful attempt at beefing up transit options in the northwest-suburban county since MARTA, the Metropolitan Atlanta Rapid Transit Authority, was created in 1965. MARTA was initially envisioned to serve the city of Atlanta and its five core counties, including Cobb and Gwinnett.

But in repeated referenda beginning in 1965—and as recently as 2019—Gwinnett voters have rejected attempts to extend heavy rail into the county. The early defeats reflect Gwinnett’s status as a white-flight suburb—a place that, following desegregation in Atlanta during the civil rights movement, grew rapidly with white people fleeing the city. In the 1960s and 1970s, attempts to expand MARTA were defeated in campaigns characterized by heavily racialized rhetoric, with white voters associating the train service with the Black Atlantans they’d moved to the suburbs to avoid living near.

Today, though, the demographics of Gwinnett County have changed. It’s the most diverse county in Georgia. Over a quarter of its residents were born abroad, one in five speak Spanish, and a trip to Lawrenceville, Lilburn, or Buford Highway, lined with storefronts and restaurants in languages as diverse as Vietnamese, Amharic, and Spanish, reveals the wide array of immigrants -from East Asia, Africa, South and Central America, and beyond—who call the Gwinnett home. Cobb County has also changed demographically and politically as well; once reliably Republican, it’s now considered a bellwether of Georgia’s emergent status as a swing state.

Better public transit, said Chany Chea, communications director for the AAAF—would also help immigrant elders, particularly from Gwinnett’s various Asian communities. “There’s a lot of Asian American seniors who don’t drive and rely on getting rides or taxis or transit,” Chea explained.

The increase of bus routes if the referendum is passed raises hopes for many community members in both counties. “Limited schedules make it difficult to get to work, medical appointments, school, and social gatherings,” Sarwar explained. A better and expanded transit system “would empower me to design a schedule that works for me. Rather than having my life revolving around the bus,” she said.

Whether or not the transit referendum passes though, could be partly dependent on how informed voters are about the issue. It’s not clear how much outreach Gwinnett County has done to immigrant communities, but Gwinnett County did post a video about the referendum with Spanish subtitles. Much of the outreach, it seems, is being done by organizations such as AAAF and Gwinnett county’s chapter of the NAACP, who have been trying to inform the county’s immigrant and minority residents about the issue.

At the AAAF event, Brian Ramirez was trying to let people know how important this referendum could be for many people’s everyday lives. “I know first-hand how much better public transportation could have helped my family,” Ramirez told the attendees. “And I know there are so many families in Gwinnett facing that same struggle today.”