“They will leave me an envelope with all the documents and passports of my siblings so that I can become their legal guardian”

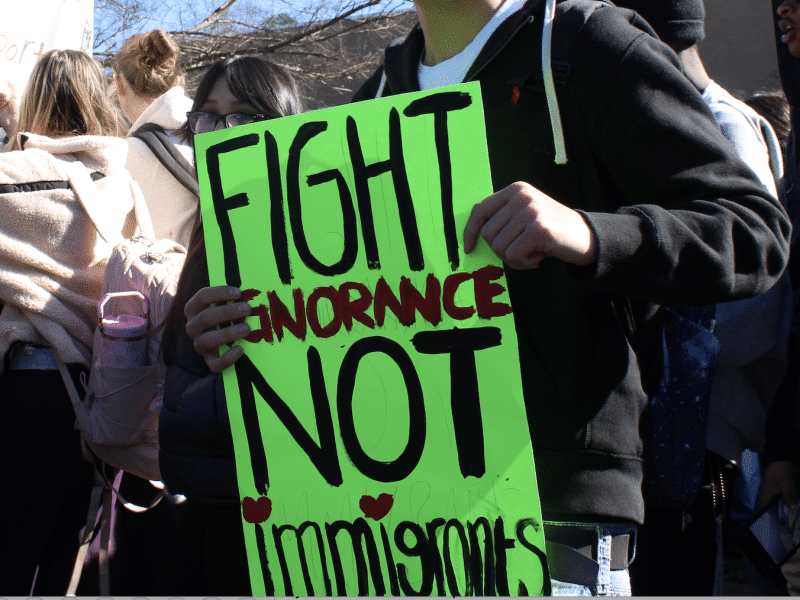

285 South spoke with children of farmworkers who gathered at the Georgia Capitol; many described steps their families were taking to protect themselves from immigration officials.

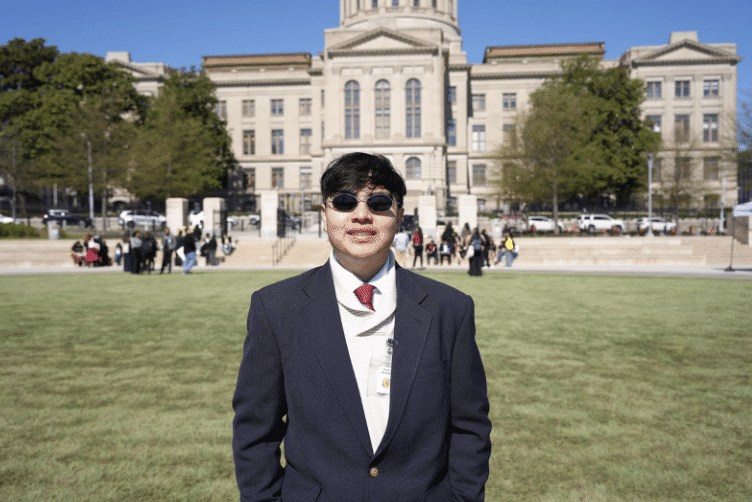

Bryan Montaño sat on the steps of Liberty Plaza across the street from the Georgia Capitol as he talked about his childhood memories in the fields of South Georgia. He would wake up at 5 a.m., he said, and spend at least eight hours under the sun, picking tomatoes and other vegetables alongside his parents. They wouldn’t come back home until around 3 p.m., when his parents finished their work.

He’s now 18 years old and a student, and on March 21st, he traveled 180 miles to the Capitol to speak to state representatives and advocate for those who couldn’t be there, or might have been afraid to come—like his parents, who are farmworkers, and are not documented.

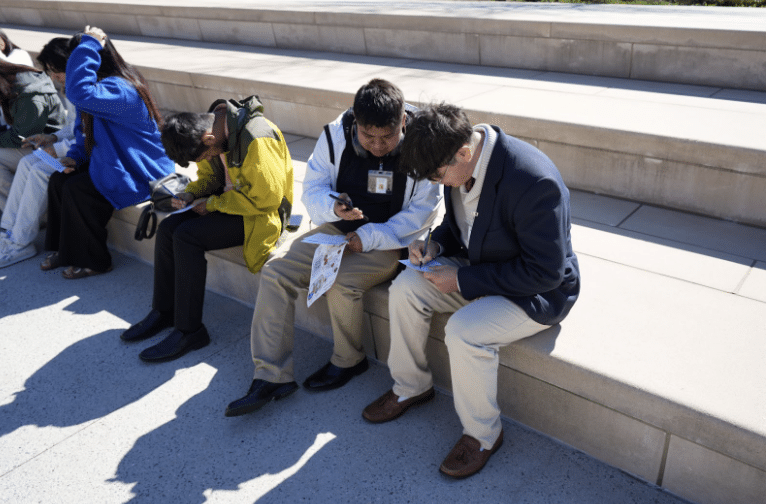

Bryan joined students from Abraham Baldwin Agricultural College, Valdosta University and the University of North Georgia, at the Farmworking Families at the Capitol event—an opportunity for the children of farmworkers to share their families’ stories with lawmakers. Now in its fifth year, the annual gathering is sponsored by the Latino Community Fund–Georgia, the largest advocacy organization for Latinos in the state.

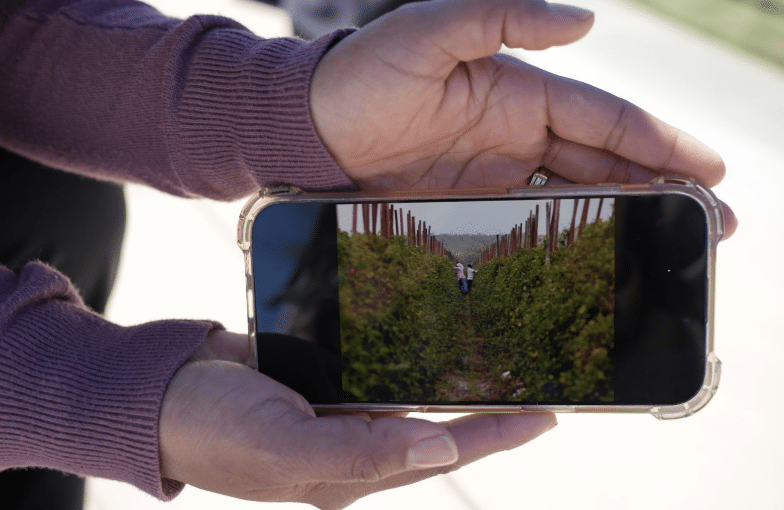

This year, though, has been different, as farmworkers have been bracing themselves and trying to prepare for an uncertain future in the country under a new presidential administration. Georgia is one of the top five states to use the H-2A visa program, which allows foreign nationals into the United States for temporary agricultural work. About 60 percent of agricultural jobs are filled by H-2A workers—but a large share of farmworkers are still undocumented. Many undocumented farmworkers in Georgia are feeling the chilling effect of President Donald Trump’s immigration policies, said Patricia, who was at the Capitol on Friday for the event, and has been harvesting crops in fields throughout the South for more than 14 years. People close to farmworkers also told 285 South that they’re afraid to go to work but still need to provide for their families. They’ve been taking extra precautions to protect themselves: everything from leaving their homes earlier to check for law enforcement to preparing guardianship for their American children in case they’re detained and deported.

Bryan, the eldest of four siblings (ages 14, 10, and five), said that in the first few days after Trump took office, his parents didn’t go to work. They couldn’t stay at home for long, though, he explained, because they still needed to pay for their rent and put food on the table.

His parents have made changes in their routines to try to keep themselves safe. “My mom doesn’t go grocery shopping anymore,” Bryan said—she used to go twice a week. “She is too worried about getting caught by immigration officials and being sent back to Mexico.” Now Bryan buys the groceries.

As another precaution, every morning, Bryan’s parents leave early for work so they have enough time to see if there are any checkpoints on their route, and that there are no immigration enforcement officials waiting for them at the field. “They’re not in such a hurry anymore,” he said. “It’s better to be safe and sound than to be in jail or worried about being deported back to Mexico.”

Bryan’s parents also entrusted him to take care of his younger siblings, in case they’re taken by immigration officials, he told 285 South. “If anything happens to them, if they are deported to Mexico, they will leave me an envelope with all the documents and passports of my siblings so that I can become their legal guardian,” Bryan said.

Bryan isn’t the only person stepping up to take care of U.S. citizen children born to undocumented farmworker parents. Patricia, a Guatemalan American citizen who works in the fields of Valdosta in South Georgia and Jennings in North Florida, said she’s supporting fellow farmworkers. This year, a friend in Immokalee, Florida, asked Patricia to become the legal guardian of her children if she ever gets deported.

“I think that one of the things that has shocked me the most has been experiencing that situation firsthand,” Patricia said in Spanish.

Most of Patricia’s friends in the fields of Georgia and Florida are making similar plans. “The community has a lot of fear because we don’t know how things can change,” she said. “You don’t know if you leave home with your lunch and won’t be able to come back to pick up your kids from school.”

She said children are having nightmares and are stressed at school because they fear their parents will be deported.

“It’s not fair that people live in fear, it’s not fair that people who contribute daily to this country’s economy, which generates a huge social and economic impact, are afraid to go out to work,” Patricia said. “We don’t want to steal; we don’t want to harm anyone; we just want to work freely and be treated with dignity.”

Bryan says he hopes his visit to the Capitol will change how state representatives see legislation affecting farmworkers. “I hope that with what they’re doing at the Capitol, we can see a difference so that farmworkers don’t feel like they just work and work but never see a change.”

*This story has been updated to remove a reference to Bryan’s location to protect his privacy.