Between trips to Costco and Chick-fil-A, 12-year-old Habiba from Gaza makes herself at home in Atlanta

Injured in the Gaza war, Habiba came to the metro area for medical treatment through Heal Palestine, which has organized trips to the U.S. for 30 injured Gazan children—still just a minuscule fraction of the war’s wounded.

Like any Metro Atlanta preteen, Habiba is obsessed with taking selfies. She loves playing around with filters on her iPad. When she’s not doing that, she’s most likely watching Turkish or Indian soap operas. Her aunt, 31-year-old Heyam, is constantly trying to regulate Habiba’s screen use, redirecting her to study when she can. She’s hoping it will get easier once Habiba starts online classes later in January.

In late December, Habiba and Heyam were hanging out in Mableton, around 15 miles west of Atlanta; they were staying with Yasmin, a Palestinian American who works at a local hospital. Yasmin’s mother, Jamila—and her sister and cousin, and their pet parrot—were all there, too, visiting from Ohio for the holidays. It was an unusually relaxed day after a very busy two weeks, in which Habiba and Heyam had been taken around to a variety of iconic Atlanta and quintessentially American spots: Zoo Atlanta, the Georgia Aquarium, Target. The highlights? For Heyam, it was Costco, which she described as “beautiful,” and where she snagged a pair of Harry Potter pajamas. For Habiba, it was the chocolate milkshake at Chick-fil-A. “Very good,” she said in Arabic, giggling.

Habiba sat on the living room couch wearing a green sweatshirt with the logo of the nonprofit Heal Palestine on the front. It was her second outfit that morning—earlier, she had emerged from the bedroom in a hot-pink sweatsuit. Her hair, combed neatly and pulled into ponytails on either side of her head, framed her face, which lit up often in a smile.

Within minutes of my arrival, Habiba was eager to perform—standing in front of the television, belting out songs in Arabic that she learned in school. Jamila said this was totally normal—Habiba loves to sing and dance in front of an audience. “We are in Gaza,” Habiba sang. “We in Gaza dream of peace.”

Habiba is from Gaza, and she is in Atlanta, accompanied by her aunt Heyam, for surgery after an Israeli strike left her with injuries to her skull and abdomen.

Sitting on a couch in a typical suburban living room, Habiba looked like a regular kid. But if you looked closely, the front right side of her head was caved in slightly. Heyam, sitting across from Habiba in the living room, pressed gently on the damaged part of Habiba’s head. It was soft, where it should have been hard. “It hurts a little bit,” said Jamila, translating for Habiba.

Less than a year ago, Habiba had been in Khan Younis, in southern Gaza. She and her family, like hundreds of thousands of other Gazans, had fled there after being forced from their home at the beginning of the war. In January, they were living in a makeshift tent by the beach—in a designated humanitarian zone where the Israeli military had instructed families to flee for safety.

That safety proved to be temporary.

On January 23, Israeli military forces escalated their attacks on Khan Younis, killing at least 40 Gazans. The tent where Habiba’s family was taking shelter was hit. “Everything lit up on fire. So they all got burned. That’s how her mother died. Her mother burnt to death,” said Jamila, a volunteer with the nonprofit Heal Palestine, translating for Heyam, who speaks Arabic. “A lot of them burnt to a crisp. You couldn’t tell who they were.”

“Everything lit up on fire. So they all got burned. That’s how her mother died. Her mother burnt to death.” – Jamila, a volunteer with the nonprofit Heal Palestine, translating for Heyam, Habiba’s aunt.

Habiba’s mother, Imani, was 37 years old. Habiba also lost her 9-year-old sister, Nour, and her uncle and her three cousins. Habiba was initially presumed dead, too, but 24 hours after the attack she was found alive—albeit gravely hurt. She was treated first at a local hospital in Gaza. In February, after receiving authorization for further medical treatment abroad, Habiba was able to be evacuated to Egypt. But the extensive injuries to her head meant Habiba needed a cranioplasty, a complicated procedure involving the insertion of a metal plate into her skull, that she wasn’t able to receive in Egypt. Heal Palestine, an organization founded in January 2024 to support children in Gaza, was able to get an Atlanta-area hospital to agree to carry out the procedure.

Arriving in Atlanta

On December 14, 2024, Habiba sat smiling in a wheelchair as Heyam, her appointed guardian since her mother’s death, walked alongside her down the international arrivals terminal at Hartsfield-Jackson airport in Atlanta. The pair were welcomed by a crowd of around 150 people, holding signs and chanting “Ha-bi-ba, Ha-bi-ba, Ha-bi-ba!”

Since Heal Palestine was founded just a year ago, the organization has brought 30 Gazan children to the U.S. for medical treatment—many of them amputees. Habiba was the 27th to arrive, and the first to come to Atlanta.

Israel’s war in Gaza, which many human rights organizations have characterized as an unfolding genocide, has hit children particularly hard: A September 2024 analysis by Oxfam found that more women and children had been killed in the first year of the conflict than in any other single-year period around the globe over the past two decades.

Of the more than 45,000 Gazans killed since October 7, 2023, at least 14,000 have been children, though the death toll may be up to 40 percent higher, according to a recent analysis. (Nearly half of Gaza’s population is under 18 years old.) The United Nations reports that young people who have survived the attacks now make up the largest cohort of child amputees in modern history.

“This war obviously has been so hard on our spirits, and seeing a child here, it’s healing for us as well,” said Ghada Elnajjar, a Palestinian American with family in Gaza, who also volunteers with Heal Palestine, and who was at the airport to greet Habiba.

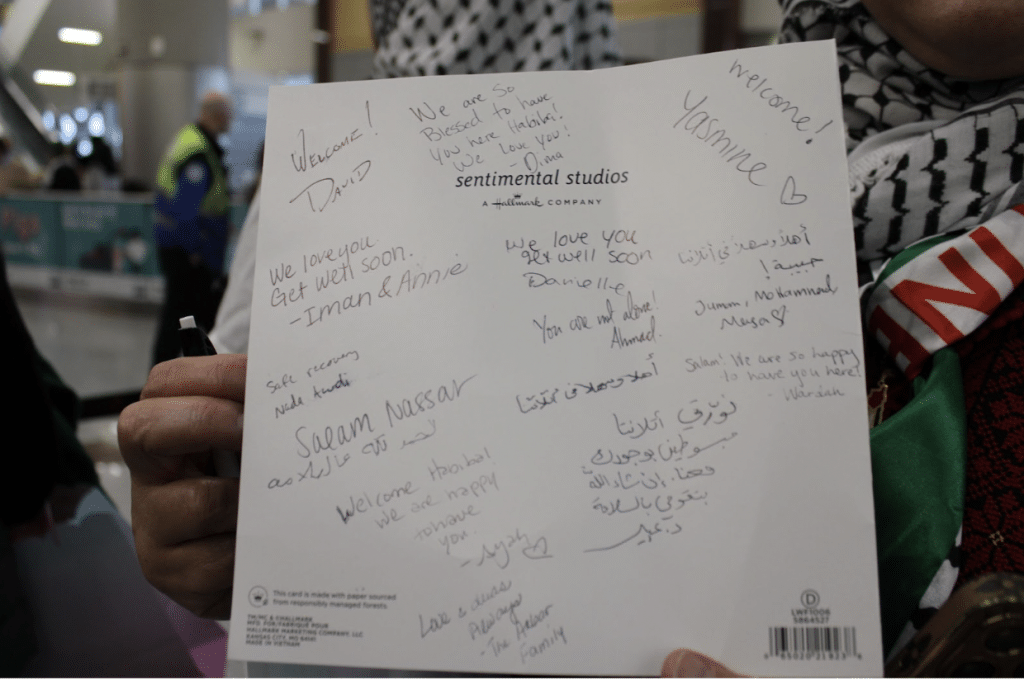

Jawahir Kamil, a Metro Atlanta resident who has been a consistent presence at the Atlanta rallies in support of Palestine over the last year, was also at the airport. She was trying to write a card for Habiba that she’d ask others to sign, but the tears flowed more easily out of her than words.

“It’s really a lot,” she said, sighing. “I don’t know what to write. Like, what are you going to write? What are you going to write?” After a few moments, she began writing in black ink, in Arabic. “We love you. We love you. We all here are your family.”

The near impossibility of getting out of Gaza

The war has left Gaza’s medical infrastructure all but destroyed. The hospitals that have remained functional are operating at extremely limited capacity, hit by everything from fuel shortages to raids by Israeli forces. As of this month, an ever-growing waiting list of those hoping to leave for medical treatment reached 12,000, with the World Health Organization estimating that, at the current rate, it could take up to ten years for those who need urgent care to be evacuated.

That Habiba and Heyam were able to evacuate to Egypt in February 2024 was itself remarkable. In the early months of the war, getting out through the southern crossing at Rafah was already a complicated process, requiring approvals, people in the know about how to apply to leave, and a lot of money: at least $5,000 per adult and $2,500 per child. In May 2024, Israel seized full control of the Rafah border, further diminishing Palestinians’ chances of accessing medical care—or leaving the war zone at all.

For around eight months, Ghada, the Heal Palestine volunteer, has been working with others to bring another Gazan child to Atlanta: Yassine, an 11-year-old who the organization said lost both of his legs in April in an Israeli strike. The community here was ready for him. They even found an Atlanta hospital to provide him free treatment. But Yassine’s mother, who needs to travel with him, couldn’t get permission to leave Gaza.

Heal Palestine, Ghada explained, submitted Yassine’s case to the State Department, requesting he be allowed to come to the U.S. for prosthetic legs. The State Department, in turn, submitted his case to the Coordination of Government Activities in the Territories (COGAT), the Israeli unit that facilitates humanitarian initiatives. “COGAT looks up the list for their own security interest, meaning whether or not the children and their guardians are allowed to evacuate,” Ghada said. “Then they will either authorize or deny.”

Yassine’s mother was denied, she continued—multiple times: “They just say ‘security block,’ that’s what they call it.” In Ghada’s experience, denials have been common. “One time we worked on eight kids,” she said. “Maybe two were evacuated.”

285 South reached out to the U.S. State Department for a comment on Yassine’s case, and a spokesperson replied in an email, saying that they could not provide information on specific cases. The spokesperson said: “The approval process requires coordination with medical organizations and the Government of Israel, which approves individuals for departure. The United States does not have authority to determine which patients are medically evacuated. The United States continues to advocate for timely approvals for departure from Gaza of ill and injured children who cannot receive adequate care in Gaza.”

Other avenues for Gazans to leave, like applying for asylum or for refugee status, are incredibly challenging, according to a December 2024 investigation published in the Guardian. “Their asylum claims require a higher burden of proof,” Amira Ahmed, an immigration attorney with Project Immigration Justice for Palestinians, told the outlet. And despite the fact that Gazans are fleeing attacks by Israel’s military, said Mike Casey, a former State Department official, claims for asylum or refugee status based on violence emanating from Israel—a U.S. ally—are rarely approved.

“Yassine’s been denied every single time,” said Ghada, tearing up. “Seeing really hard cases that were denied evacuation is the hardest part. Because seeing the pictures of the injured children is so haunting.”

But, she said, “you can’t just stop. You have to keep going, and you have to submit more cases.”

“Seeing really hard cases that were denied evacuation is the hardest part. Because seeing the pictures of the injured children is so haunting.” Ghada Elnajjar, Heal Palestine volunteer

In February 2024, President Joe Biden announced that some Palestinians living in the U.S. would get protection from deportation for 18 months, a policy called Deferred Enforced Departure. Two months later, the White House reportedly considered a policy that would allow some Palestinians in Gaza—those with family members who are U.S. citizens—to come to the U.S. “We are constantly evaluating policy proposals to further support Palestinians who are family members of American citizens and may want to come to the United States,” White House Press Secretary Karine Jean-Pierre said in early May. 285 South asked the State Department for an update on that proposed policy, but at the time of publication, had not received a response.

Since she arrived in Atlanta last month, Heyam said, four of her siblings have been injured in bombings. “Every time my phone rings, or every time I hear there was a bombing in the area where my family is, I start crying because I don’t know if the phone call, or what I heard of, is if somebody is gone. I want the war to stop, so I can stop being afraid, period.”

Atlanta’s warm welcome

Since the moment she arrived in Atlanta, Habiba has been showered with attention, not just from doctors, but from supporters who have volunteered to show her around. She wears a little turtle charm around her neck—a souvenir from her trip to the Georgia Aquarium. Her nails are painted red with golden sparkles—Yasmin had painted them for her. On her feet, fuzzy white slippers with smiley faces on them—a gift from the mother of her main host family. When I visited in December, plans were in place to take her to the Winter Lantern Festival at the Gas South Arena and to grab ice cream afterwards at Wowbooza, a Palestinian-owned cafe that sells stretchy ice cream.

Habiba was cuddled up on the couch in those slippers with her iPad when the phone rang. It was her eldest sister, Yasmeen, calling from Gaza.

Habiba’s energy changed. She talked excitedly, straining to see her sister’s face. It was dark in Gaza—there was no electricity, her sister explained, and the internet connection was spotty. Heyam rushed to the phone, and others in the house also joined, eager to meet Habiba’s sister. Everyone seemed to be bouncing around, poking their heads around the phone, wanting to say hello.

With all the commotion, Jamila had nearly forgotten about the za’atar bread with cheese that she had put in the oven for breakfast. She took it out just in time.

As I left the house, Habiba rushed to me. “Nice to meet me!” she said excitedly. Everyone laughed. She tried again, but still couldn’t quite get the sentence.

Just before walking out the front door, she ran up to me again. In perfect English she said, “Have a nice day!”

Postscript:

On January 7, Habiba underwent a successful cranioplasty in an Atlanta-area hospital, recovering as snow turned the metro area into a winter wonderland. In about six weeks, Heyam will take her back to Egypt, where her grandmother and sister are currently living. They’ll stay in temporary housing until—or if—they can reunite with the rest of their remaining family in Gaza.

On January 17, Israel’s cabinet voted to approve a ceasefire agreement reached between Israel and Hamas on January 15. As part of the deal, aid groups are hoping Israel will lighten travel restrictions on those seeking medical care.

In a social media post, Heal Palestine said it had “cautious optimism” about the announcement.