“I think we’re going to need all the support that we can get in the next four years”

The returning president has promised mass deportations, expanded workplace raids, and a crackdown on protest. Here’s how some Atlanta-area immigrant-rights groups are getting their communities organized.

“The first reaction every time a conservative administration comes to power is to hide,” says Luis Zalvidar, the state director for the Georgia chapter of CASA, a national nonprofit that advocates for immigrants and Black and working-class communities. “A lot of people default into, OK, let’s not make any trouble.”

But as former president Donald Trump prepares to retake the White House next month, Luis, who is originally from Peru, is urging the opposite approach. As they face increasing threats to their safety and well-being in this country, he says, now is the time for immigrants to make their presence known: “The main reason why people do not understand the magnitude of the immigrant experience and our contribution to societies, [is] because a lot of people are just not saying [it].”

CASA Georgia is just one of many advocacy organizations in the metro area gearing up for what could be an unprecedented wave of attacks on immigrants in the U.S.—and grappling with some of the fears that the prospect of those attacks is already generating.

On the campaign trail, Trump promised mass deportations that could affect both undocumented immigrants and others, such as those here under Temporary Protected Status (TPS). He’s vowed to suspend refugee resettlement. And he’s threatened to carry out a punishing program of raids, not just on workplaces where undocumented people might be employed but in spaces not previously subject to federal raids, like schools, churches, and hospitals.

How many of Trump’s promises will come to pass is now a major question facing immigrant advocacy and other civil rights organizations. In Georgia, those policies could be facilitated by a Republican state leadership that, in the last session, passed legislation making it easier for local law enforcement to refer undocumented people to federal immigration authorities. According to advocates 285 South spoke to, more legislation targeting immigrant communities may be on the horizon when state lawmakers reconvene in January, a week ahead of Trump’s inauguration.

To prepare for the incoming administration, local immigrant rights groups are helping people understand their rights, preparing legal teams to challenge deportation proceedings, recruiting volunteer lawyers to visit detention centers in rural Georgia, and spreading the word about specific needs that community members might be able to meet—like access to spaces for organizing.

At the same time, they’re walking a fine line, says Murtaza Khwaja, the executive director of Asian Americans Advancing Justice–Atlanta (AAAJA), the largest legal organization in the Southeast representing people of Asian and Middle Eastern origin. “We don’t want to spread fear,” Murtaza says. “There’s limitations to what anyone can do, and there’s guardrails in place that can help protect some of it or that will make some of it more difficult.”

Education, Luis says, is power: “The main thing is that if people just know their rights, they will be pretty OK.”

Educating communities on their rights

One area of focus, then, is “Know Your Rights” training: workshops where groups can educate community members on what to do if agents from Immigrations and Customs Enforcement (ICE) show up at their door—or their workplace. CASA, where Luis works, has trainings planned in the next few months in DeKalb, Gwinnett, and Clayton counties, areas of metro Atlanta that have particularly robust populations of immigrants. People should know, for instance, that they don’t need to open their front door unless an immigration agent presents them with a warrant. “They don’t have to give information unless there is a warrant,” Luis says. “Just wait for a lawyer. [If] people just do that, they will be pretty OK.” (Here’s CASA’s full “Know Your Rights” guide.)

AAAJA, meanwhile, has four such workshops planned—on an abbreviated schedule. “We are definitely front-loading some of them this year,” Murtaza says, out of recognition that people might need this information quickly.

“There’s limitations to what anyone can do, and there’s guardrails in place that can help protect some of it or that will make some of it more difficult.” – Murtaza Khwaja, Executive Director, Asian Americans Advancing Justice – Atlanta

Workplace raids, common during the first Trump administration, are another area of concern for advocates such as Elizabeth Zambrana, the legal director at Sur Legal Collaborative. “What rights do workers have when there is a raid? And what rights do employers have? Do they have to let ICE on their property?” says Elizabeth, whose organization supports workers in hazardous situations, like the Gainesville poultry industry. Many of her clients are recipients of Deferred Action for Labor Enforcement (DALE), a Biden administration initiative that extends protections to undocumented workers who are victims of, or witnesses to, instances of workplace abuse. With Trump expected to end DALE once he takes office, Sur Legal has been hurriedly working since the election on submitting requests for extensions.

Though workplace raids occurred during the first Trump administration, the president-elect may now expand the list of places where ICE agents look for undocumented people. According to past policy, ICE has avoided “sensitive” locations like churches, schools, and hospitals; Trump is also expected to end that policy. Sur Legal and other groups are preparing trainings for different contexts. “Like, knowing your rights when ICE comes to your home,” Elizabeth says, versus the workplace. “What kind of warrants do they need?”

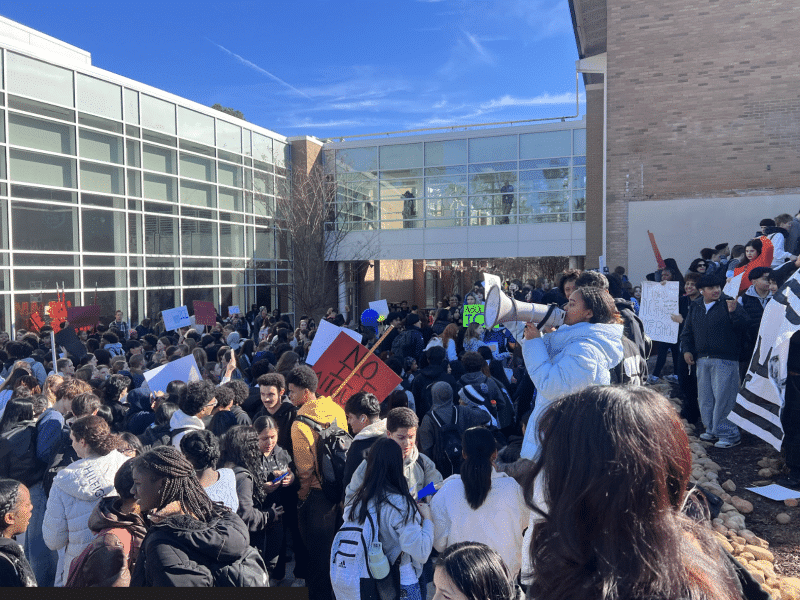

While Latino groups are educating constituents on dealing with ICE encounters, Arab and Muslim organizations like the Council on American Islamic Relations are focused on educating members on their free-speech rights. As in his first term, Trump is again expected to crack down on protest—particularly protests against Israel’s ongoing and expanding war in Gaza, Lebanon, and other parts of the Middle East. The 2024 Republican Party platform included a provision promising to “deport pro-Hamas radicals,” which may mean the incoming administration will target foreign students in the country on a visa. The Georgia chapter of CAIR has already held workshops on free speech in Clarkston, Roswell, and Alpharetta, where there are large Muslim communities, and have two more events planned in the metro area in January. They’ve also put together a range of “Know Your Rights” guides, on everything from being stopped at the airport or border to employment discrimination.

Lawyers needed

In the event that immigrants are arrested by ICE agents, they may end up at one of six immigration facilities in Georgia—the most widely known being Stewart Detention Center, in Lumpkin, and the Folkston ICE Processing Center in South Georgia.

If someone does get stuck in detention, they might have trouble finding a pro bono lawyer to represent them. That’s in part because the Southern Poverty Law Center, one of the few groups offering pro bono representation to people incarcerated in these facilities, eliminated its entire immigrant justice team last summer.

To help fill the gap, the American Immigration Council, a national advocacy group, is actively recruiting volunteer attorneys, interpreters, and translators in Georgia and throughout the country. One way of meeting the needs, says Rebekah Wolf, director of the council’s Immigration Justice Campaign, is by training attorneys—including those that may not have an immigration law background—to be able to help with a wide range of immigration cases.

“We’re making sure that we have the legal expertise on our teams and the materials to help attorneys not just do an asylum case, but do all the other kinds of things that we can do to protect people and their rights if they’re arrested or detained by ICE,” Rebekah says. She expects there will be an increased need for representation for immigrants who have been living in the U.S. for years and are arrested on an unrelated offense—even something like driving without a license—and put into deportation proceedings, or people with old removal orders. Those are the types of people Trump’s administration may target first, she says: “He has said that that’s what he’s going to do.”

Caring for family members—and building networks of support

As lawyers gather legal resources, others are preparing community members for the worst-case scenario—they’re deported and separated from their families. “Unfortunately,” says Sur Legal’s Elizabeth Zambrana, whose parents are from Mexico and Nicaragua, “there is also a big aspect of safety planning.”

Many of the people Sur Legal works with, she explained, are single moms and/or primary breadwinners. She’s been encouraging them to make a plan “in the event that you’re detained or picked up in a raid. Making a plan for childcare or care of other vulnerable family members that rely on you. Making sure that documents are in order. If they have kiddos, making sure that those passports are current, they have copies of important documents, like their birth certificates or Social Security.”

One of the most essential needs at this moment, says CASA’s Luis Zalvidar, is to create “networks of solidarity” that can provide safety—which means individuals building relationships with groups like nonprofits, churches, and community associations. “So if, for instance, there is going to be a raid close to an Amazon warehouse: Well, there are now Amazon workers that are unionized, right?” he says. “So working with a union to make sure that people know that that’s happening and they can go to the space where these folks are working—that will be a thing.”

Sur Legal is hoping to form more connections with people interested in understanding the intersection of labor and immigration, Elizabeth says: “In a perfect world, there would no longer be [a need] for us, because our community knowledge would be so built up.” But until that day comes, Sur Legal will be offering training and joining up with as many groups as they can. “I think we’re going to need all the support that we can get in the next four years,” Elizabeth says.

“In a perfect world, there would no longer be [a need] for us, because our community knowledge would be so built up.” – Elizabeth Zambrana, Legal Director, Sur Legal Collaborative

Organizations like CAIR Georgia, Advancing Justice, and the American Immigration Council said they always welcome volunteers who can help with know-your-rights training, provide legal representation, or respond to calls to action.

Finally, Luis said, his organization is urging concerned people to simply offer up physical space—and time. “If you want to help, find a community space in your neighborhood where know-your-rights training can happen,” he said. “And if you really want to help, help us knocking the doors in your neighborhood. Ask if there is anybody who will be affected by any immigration policies—I can promise everybody has an immigrant in their block, right? So meet with them, invite them over. Even if it is two or three, people will send somebody out, and have that conversation, because that is what really is needed.”