Immigration check-ins can be daunting. But in Atlanta, volunteers are showing up to help

Outside federal offices downtown, supporters offer snacks, know-your-rights cards—and, in some cases, connections to legal resources

On a June morning, the line formed before dawn along tall wrought-iron gates on Ted Turner Drive. Most people carried paperwork, and some had children with them. They waited for immigration court dates and check-ins at the downtown field office of U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), where people who’ve previously been detained or apprehended are required to meet with officers. Edna waited in line with her sister-in-law, Stephanie.

Edna, who was born in Mexico, was there for her own check-in with ICE. But the two women were more worried about Edna’s brother Juan—Stephanie’s husband. In rural Middle Georgia, Juan had been arrested on his way home from work, and then taken into ICE custody. For five days, Edna and Stephanie weren’t able to locate Juan in ICE’s online detainee locator system, since they didn’t have his “alien ID number.” Finally he called them from detention in Atlanta. He had been driving legally, Stephanie said, “but the cop pulled them over because he fit a certain demographic.” After Edna’s annual check-in, they planned to meet with an attorney for their loved one.

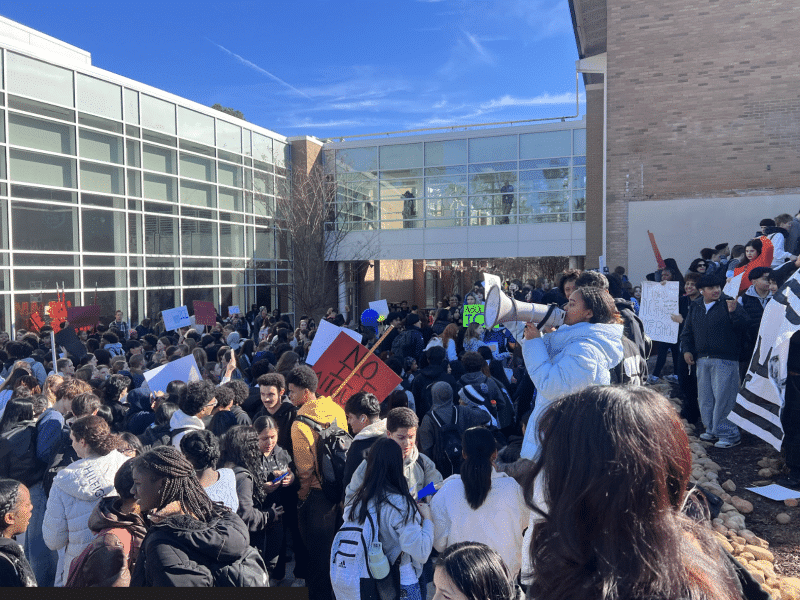

The line outside the ICE office grew to around 50 people. This morning, everyone was greeted in Spanish and English by volunteers from Casa Alterna, an Atlanta-based organization that has been offering “radical hospitality” to Georgia’s immigrant communities for 20 years. The group gave rise to El Refugio, now a separate organization that offers support—and a free place to sleep—to people visiting incarcerated loved ones at the immigration detention facility in Lumpkin.

This year, following President Donald Trump’s return to the White House, Casa Alterna founder Anton Flores-Maisonet started Compas at the Gates—short for compañeros, or companions. Compas organizes volunteers at “the front lines of the worst of this machine,” as Anton put it: the ICE office in downtown Atlanta. They pass out know-your-rights cards, snacks, and teddy bears for the kids, and also offer overnight housing and help with transportation. They provide what Anton calls a “humane presence.”

While some people lined up for check-ins with ICE agents, others were there to see an immigration judge. Some people wore GPS ankle monitors, signaling that they were participants in ICE’s “Alternative to Detention” program. Most enter immigration court without legal representation, and Compas at the Gates volunteers work “one-on-one to understand each person’s situation, connect with trusted attorneys for any complex cases, and maintain a calm, compassionate presence, always mindful of everyone’s privacy and safety,” Anton said.

The people showing up for appointments “want to believe that our system is democratic and just, and that our courts are impartial, and that they’ll get a fair hearing,” said Anton—who sees it differently. Casa Alterna board member Hannah MacNorlin, an Atlanta immigration attorney, explained that people with citizenship or legal residency papers can’t be removed from the country without due process, but undocumented people have no such protection: In immigration court, all that’s needed to deport somebody is their identity. “There [are] literally no checks on ICE and there never have been, Constitution-wise,” Hannah said.

“This administration is expanding the cruelty that we saw at the border under the first Trump administration,” Hannah said, with record numbers of people in immigrant detention and a huge increase in detained immigrants who have no criminal charges. One concern that Hannah and Anton noted was the rising use of 287(g), a controversial provision of 1990s immigration legislation that empowers local law enforcement to act on behalf of federal immigration agencies—which has led to “constant allegations of racial profiling,” Anton said. Since Trump’s return to power, 287(g) agreements between ICE and local agencies have expanded across the states—from 135 in December 2024 to more than 800 now.

Another person in line, Fabio, left Venezuela with his family after being threatened by masked government agents—he’d tried to run for local office as a member of a party that opposed the government. “What I’m asking for here is protection for my life,” Fabio said in Spanish. He is seeking asylum for himself and his family in the States. President Trump’s disregard for constitutional law reminded Fabio of the late Venezuelan president Hugo Chavez, he said.

“If they’ve left everything familiar because of fear of persecution, then they’re seeing things here that are unfortunately reminiscent,” Anton said, pacing up and down the line outside the field office, making jokes and smiling at every person he encountered. “We as Americans need to pay attention to that.”

He called Compas at the Gates an evolving effort, saying the work could be replicated at ICE offices across the country: “We’re committed to sharing this model so others can show up with the same compassion and courage.” Anton hopes to see more people “get off their sofas,” he said, and asked: “What would you do if your family’s safety depended on standing in that line?”