In Duluth, a Korean restaurant practices a rare art: making tofu by hand

Owner Suntai Kim apprenticed with a tofu master in Seoul before opening Dubu Gongbang last year in Gwinnett County’s bustling Koreatown area.

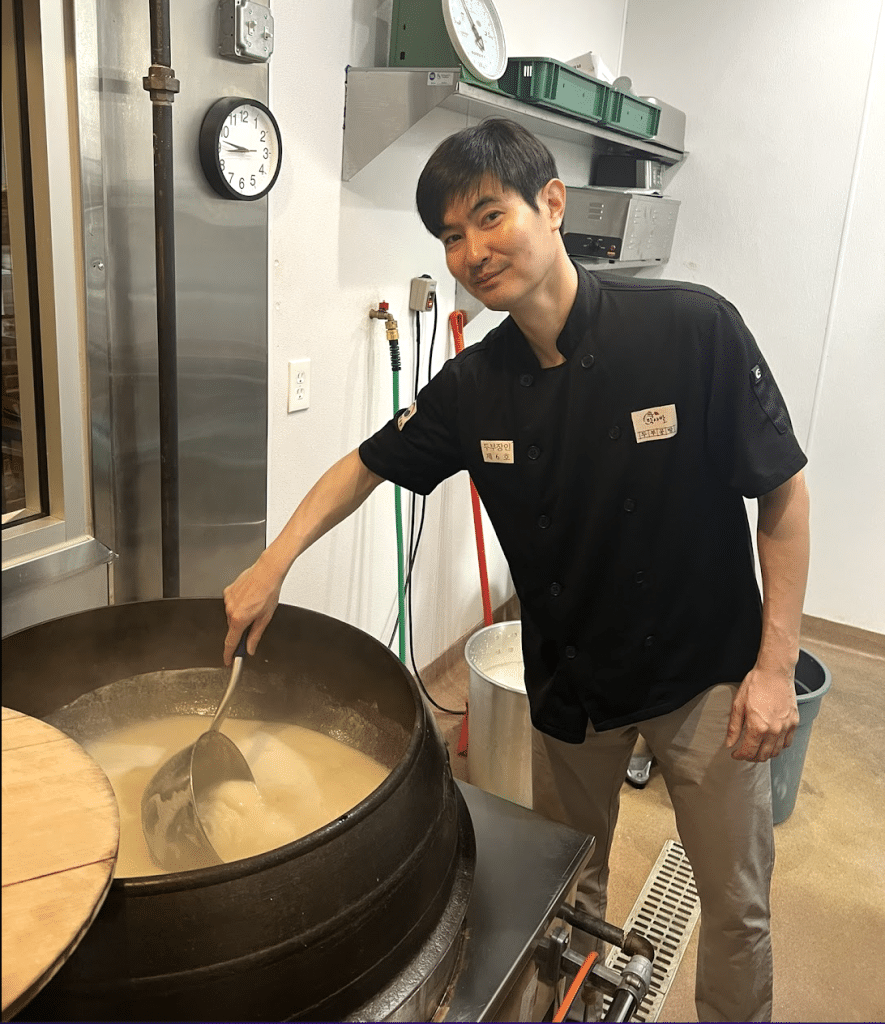

At 8:30 a.m. in a pristine Duluth restaurant kitchen, Suntai Kim feeds scoops of dripping-wet soybeans into a shiny metal vat—the bowl of a machine that will grind the legumes to a pulp, separating out the skins to create what is essentially soy milk.

It’s the day’s first task at Dubu Gongbang, the Korean eatery that Kim co-owns with his mother. In a few hours, when he’s finished, he’ll have fresh tofu—the centerpiece of his menu, and hopefully enough to feed a steady stream of customers who come looking for it. Handmade tofu is a rarity, even in restaurants in South Korea; in Atlanta, Dubu Gongbang is one of very few places it’s available.

Tofu has been around for thousands of years (it originated around 2,000 years ago during China’s Han dynasty) and is still a staple today of cuisines across Asia, including Japanese and Korean. Though there are regional variations, it’s all made by basically the same process: adding a coagulating agent to soy milk to create a solid, protein-rich, milky-white ingredient for use in stews, stir-fries, and other dishes.

At Dubu Gongbang, one of the menu’s two sections is devoted entirely to stew (known as jjigae and served in earthenware bowls) that feature soon dubu—Korean soft tofu. After apprenticing with a master tofu maker in Seoul, Kim opened the restaurant last year in a busy strip mall in Gwinnett County, which is home to about a third of Georgia’s Korean American population.

Most of the week, a dedicated employee makes the tofu. 285 South joined Kim on a Monday, when it’s his job.

For two to three hours, the action is nonstop. On the busiest days, Kim says he starts with 33 pounds of soybeans that have been soaked in water overnight; to achieve the best flavor, he sources half his beans from Iowa and half from Danyang, South Korea. After the beans are pulverized, Kim boils the extracted liquid with water in a waist-high cauldron, diligently stirring for an hour until it thickens. “You can smell some savoriness,” he says—a sign it’s ready for the next step.

Then the transformation accelerates: Kim pours in a carafe of brine that will cause the mixture to clump into curds, like cheese. Different tofus rely on different coagulants, including acids and enzymes; Kim uses saltwater from the body of water known to Koreans as the East Sea, and to others (the name is disputed) as the Sea of Japan. Then he stirs it until it thickens to just the right consistency before curdling.

“I thought it was almost like magic,” Kim says about the first time he saw the process—which, at Dubu Gongbang, customers can watch through a large window into the restaurant’s kitchen. Each cauldron of tofu makes 150 dishes. It’s laborious and time-intensive work, and the wrong amount of heat, water, or salt could result in a botched batch. Each batch is different, Kim says: “That’s what makes making tofu interesting. Making tofu by hand is an art.”

***

Dubu Gongbang may be new, but Kim is no stranger to the restaurant industry. Now 42 years old, Kim was born in Cookeville, Tennessee, while his father was earning a master’s degree in industrial engineering. When he was three, the family returned to Seoul so his father could work in the rubber manufacturing plant that Kim’s grandfather founded after fleeing the North during the Korean War.

He lived in Seoul until age 14, returning to the U.S. for boarding school and later college at Penn State, where he studied business. It didn’t suit him: Kim tried his hand at consulting in Tokyo, but he hated being stuck behind a desk. He found his real passion after he got a job managing a Korean restaurant in New Jersey: “I got hooked to the business quite fast,” he said. Kim dabbled in various pursuits—a food truck offering Korean ice cream, a cart selling Korean fusion food on Wall Street—before becoming a partner in a restaurant in Manhattan’s K-Town.

In 2020, Kim and members of his family moved from New Jersey to Duluth, drawn by what they’d learned of the Atlanta metro’s vibrant Korean community: “We didn’t know much about Georgia,” he said, except for that fact. But his initial stay there was short-lived: When Kim’s grandfather died toward the beginning of the Covid-19 pandemic, he moved back to Seoul to help manage the family business. While there, he got married, had a daughter, and became a regular at a neighborhood tofu restaurant, Dubu Gongbang, that’s part of a South Korean franchise.

He loved it so much he decided to make tofu the focal point of a new restaurant – naming it after the restaurant in Korea – that he would open when returning to Duluth. Kim ended up paying the owner to teach him to make tofu for two weeks in the master’s hot kitchen learning techniques that were hundreds of years old. The only difference is that here, soybeans were ground with a machine, rather than by hand; otherwise, Kim was surprised by the simplicity of it. “I thought it would take many ingredients to make tofu, but it was just soybean juice and salt and water,” he said. “I was shocked at how this liquid becomes tofu.”

In New Jersey, Kim’s mother had owned a cold-noodle restaurant, so that’s the first business she and Kim’s sister tackled when the family moved to Georgia: Sambong Naengmyun, which opened its doors in Duluth in 2020. They followed that with Kisoya, a Japanese katsu and udon noodle restaurant in Suwanee. Last year, Kim and his mother launched Dubu Gongbang, an independent restaurant unaffiliated with the chain where he learned the tools of the trade.

***

When it reaches the right consistency, Kim drains curds of piping-hot tofu and scoops them into a separate container. Then he brings the fresh batch over to a countertop where it’ll be added to each individual order of soon dubu jjigae warming on the stove. Spicy seafood soon dubu jjigae is Dubu Gongbang’s most popular dish, and there’s spicy oyster jjigae and kimchi jjigae, and plainer options for those who prefer less heat. Kim also serves soon dubu jjigae as part of a combo meal that also includes a choice of proteins like barbecued pork, marinated short ribs, or grilled mackerel. Meals include barley tea, sticky rice served in a stone pot, and various banchan like kimchi and fish cake.

Next, Kim ladles the remaining curds into a rectangular mold that he uses to create a firmer tofu for dishes like dubu kimchi (stir-fried kimchi and tofu) and seared dubu in perilla oil. Today he’s making black sesame tofu, so he sprinkles black sesame into the steaming curd. He gingerly folds the edges of a hemp cloth over the mixture and shakes it to remove excess water, then tops it with a wooden cover, leaning onto the mold to press it. Finally, he inverts the solid block of tofu onto a cutting board to be sliced.

Business has been good so far, and demand for Dubu Gongbang’s tofu exceeds its supply. Customers ask if they can buy it—they cannot. “What we make is barely enough to cover our customers who come into the restaurant,” Kim says, back in the rear of the restaurant to take delivery on a shipment of soybeans. “I was very impressed when I first saw how tofu was made. I wanted to share that experience with people,” he said. “It’s a lost art.”