Snapchat vs. salah: For many Muslim families, phones present both challenges and opportunities (but mostly challenges)

At a recent event, Atlanta-area Muslims gathered to discuss strategies for keeping kids safe online—and connected with God.

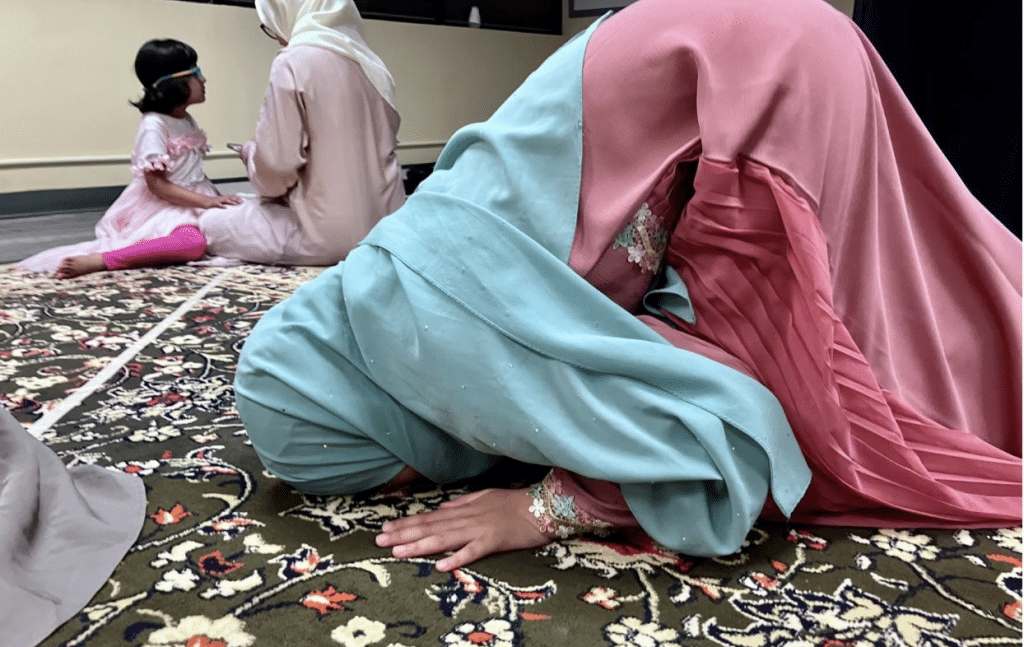

Many Muslims have experienced it: the intrusive ringtone of a smartphone, or the ding! of an app notification, breaking their concentration in the middle of prayer. From before dawn till one hour after sunset, Muslims are obligated to pray five times a day—a physical ritual that’s considered to be a conversation with God, involving recitations from the Quran, personal supplications, and bowing in the direction of the Kaaba in Mecca, Saudi Arabia.

But even there, in the holiest of places for Muslims, phones are increasingly encroaching on worship, with pilgrims livestreaming, posting updates, and taking endless selfies in front of the iconic building. “People are taking pictures, going live during the ritual of Tawaf. I found people in video calls during another ritual of Sa’i,” said Amy Rahman, who had visited the Kaaba earlier this month, and was referring to rituals in which pilgrims encircle the Kaaba, and walk between two symbolic sites. “Tawaf and Sa’i are times when we should connect with Allah, because Allah accepts our prayer during these times,” she continued. “People are busy with phones when they should concentrate on the rituals and make an effort to connect with our creator.”

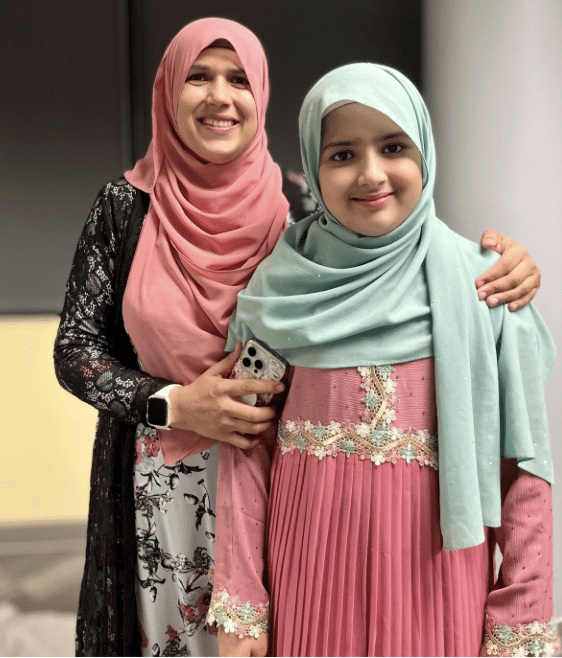

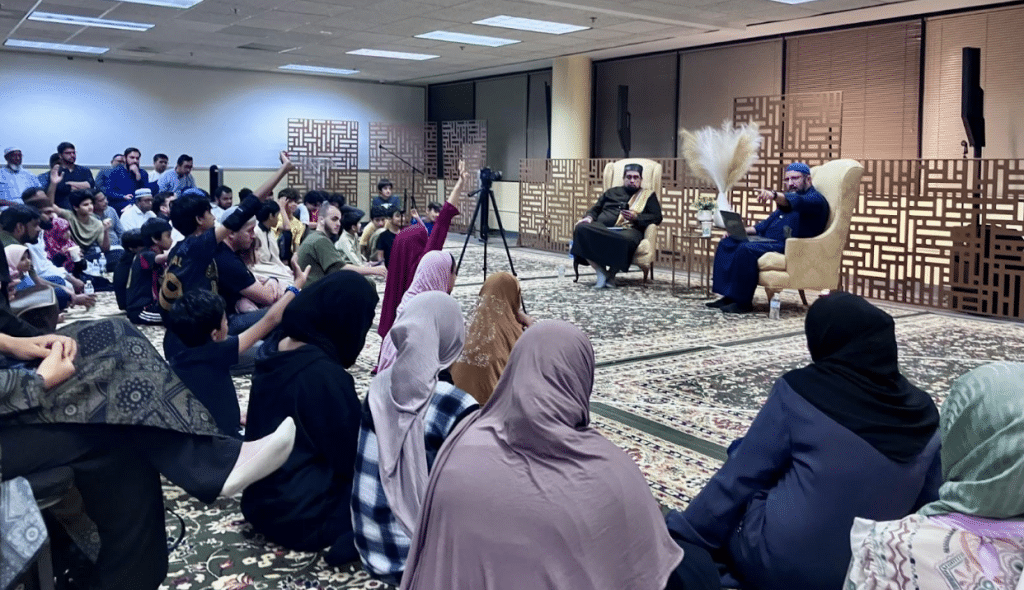

Nowadays, of course, public places from schools to movie theaters are grappling with the challenges posed by the constant presence of smartphones. In mosques and other religious settings—places that emphasize togetherness, quietude, and personal reflection—phones and social media apps offer opportunities, such as greater access to religious content, in addition to problems like shrinking attention spans. At the Roswell event, hosted by the Muslim Wellness Center, 285 South spoke to experts, parents, and kids about how they were navigating the constant dings of the phone in their most sacred spaces and moments.

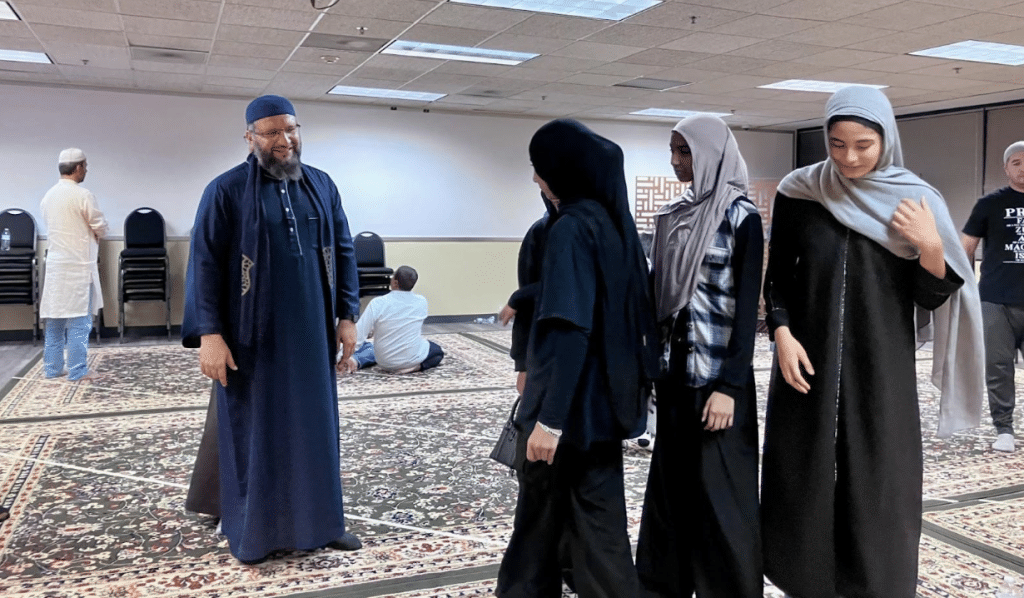

Around 150 people gathered on the second floor of a large office building on Friday, eager to hear from Salar Rasoul, an educator who calls himself the “Muslim Principal”—and, because he has nearly a half million followers each on TikTok and Instagram, a “social media imam.” Based in Toronto, Salar traveled to Atlanta to speak to young Muslims about how to balance their faith, with their phones.

In his nearly two decades of experience working in Canadian Islamic schools, Salar says he has seen a rise in phone addiction, cyberbullying, and students being lured to meet online predators. Phones and social media, he said, are contributing to growing mental health problems among the young people he works with: “Kids are cutting their hands, engaging in self-harm. I’ve seen an increase with my own eyes.”

It’s not just a problem in schools—and not just a problem for students. “Wives are saying their husbands are focused on the screen too much. During lectures, during Friday sermons, I see uncles playing video games on their phones,” Salar said. “You’re not even supposed to talk with others or play with prayer beads during that time. It’s impacting the young, but the human brain is the human brain. We all have the same addictions.”

Attendees said that they too had noticed the distractions that phones pose, sometimes leading Muslims to delay or skip prayers altogether—and setting a bad example for younger generations. Lateefa Khan, who lives in Duluth, has five kids ranging in age from five to 17, and is married to the imam of Johns Creek’s Masjid Jafar. Only her 17-year-old has a phone, Lateefa said, but she decided to attend the event to be proactive: “If I, as a 36-year-old, can’t control myself, it’s hard to expect children [with phones] to focus on religion,” Lateefa said.

“There’s a deterioration of Islamic values,” Salar said. “Social media gives you a fake sense of connection. But you’re not connected to anyone.”

The double-edged sword

Social media “can be a double-edged sword,” says Yasmeenah Massey, a Decatur-based therapist with Counseling 360. “I’ve seen Muslim youth use phones intentionally to study Islamic concepts—that’s a healthy use. But I’ve also seen them watching things they sometimes didn’t mean to watch and have to scroll past. It doesn’t have to be complete nudity, it can be girls twerking, which is normal for certain parts of society, but not what we want teenage boys having on their phone. Or even men. I don’t want my husband watching that.”

Most recently, Yasmeenah spent three years working with teens at a psychiatric residential treatment facility in Atlanta, and also worked for Georgia’s Division of Children and Family Services. Additionally, she volunteers her time every day as a “Dorm Mother” at the SAVE Institute, an alternative high school in South Atlanta that her son graduated from. She says overuse is a growing problem among her patients.

Teens spend an average of five hours a day on social media, according to the American Psychological Association—which found that the teens with the highest use rated their overall mental health as “poor” or “very poor.” Excess social media use has also been linked to higher rates of youth depression, anxiety, suicidal ideation, and self-harm. Nearly a dozen states have enacted some form of legislation concerning minors and social media—including Georgia, where last year Governor Brian Kemp signed the Protecting Georgia’s Children on Social Media Act of 2024. (That law was deemed unconstitutional after a U.S. district judge struck it down in response to a lawsuit raising concerns over free speech and fair enforcement.)

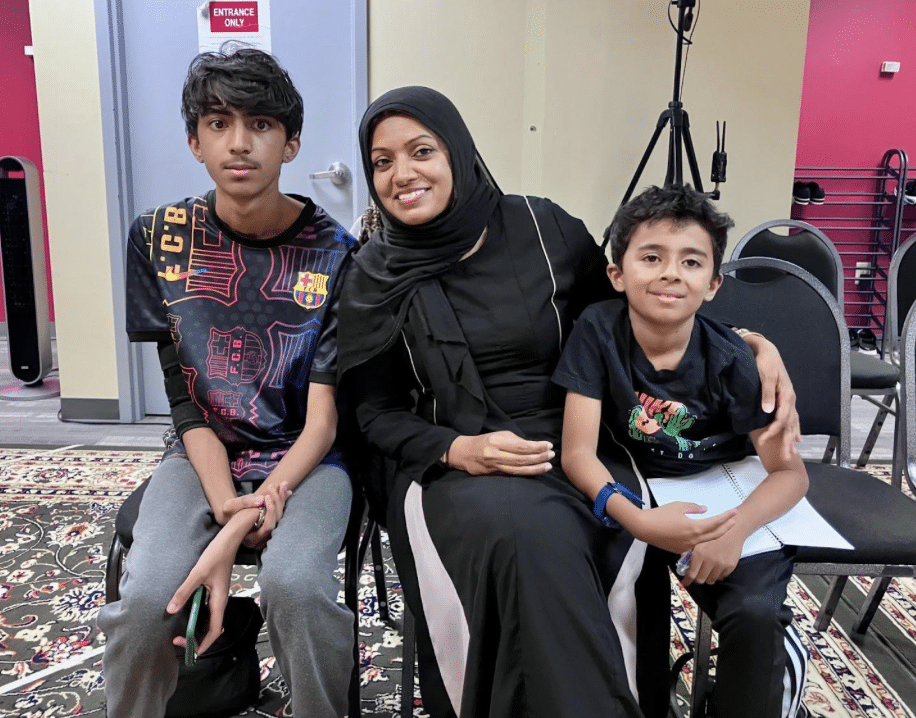

Then there’s the other edge of the sword: the notion that smartphones and social media can be harnessed in a way that will benefit users’ faith. Aeiza Shaikh, a homeopathic doctor from Lawrenceville, drove to the Roswell talk with her two sons, who she sends to Al-Falah Academy, an Islamic private school in Norcross. She came because she wanted to learn about “new tools to help us strengthen our prayer,” she said.

“Even though [my sons] go to an Islamic school, we still need this awareness,” Aeiza says. “Everyone is struggling. We want the prayers to be focused.”

The challenge isn’t limited to Atlanta-area Muslims—or Muslims at all. Amy Valdez Barker, a United Methodist pastor and an adjunct professor at Candler School of Theology at Emory University, said that, in her church, most people are concentrated on the sermons—“but then there are those who are, like, if the sermons get boring, they’re on their phone.” Amy, who trains other pastors as a leader of the Ministry Collaborative, said while it’s not polite for people to pull phones out during sermons, it could be due to ignorance around social rules: “The question is, who taught them that social boundary? If you teach that boundary in a voluntary organization, then yes, as you walk into worship there should be something that says ‘Silence your phones.’ Create that cultural expectation. But too often we get comfortable and just assume people are going to do that.”

She added that her experience had been similar to some of the attendees at the Roswell event—she, too, has seen young people “using social media as a place to connect with God,” Amy said. “My son would be a good example of that. He follows a TikTok influencer who talks a lot about faith and about God, where I feel like he’s getting some of that connection. So I think there are some who are looking to that online environment where they are getting their spiritual itches satisfied.”

Striking the right balance

During the event, organizers shared some tips for keeping children safe online, including keeping devices in open areas of the home, using technology to set app and time limits, as well as installing parental monitoring programs like Qustudio on phones or tablets. They also suggested guardians have conversations with children about the dangers of excessive social media use—and about setting rules around screen time. Aeiza Shaikh rattled off her own—no video games on weekdays, for instance. She said she keeps her sons busy with sports and homework to minimize screen time.

Aeiza’s 14-year-old son, Suheb Chishti, has a phone that he shares with his eight-year-old brother. He gets to use it only after he does his chores, he said. “My screen time use isn’t as crazy as my friends’. I feel like kids are more focused on their social media versus their religion,” Suheb said. “If I see others using it too much, I would say, ‘That phone isn’t getting you a ticket to Paradise.’”

The most persistent piece of advice offered by organizers was to keep kids away from social media and phones until they’re 18—or at least to delay it as long as possible. “Parents are saying it’s impossible, but it’s just that kids are just yelling louder and higher,” Salar Rasoul said. “I’ve never spoken to a parent who told me they wish they gave their child a phone earlier.” He gave his own son a phone when he was in 10th grade, during the Covid-19 pandemic.

“The kids in my school without phones, they’re the most social kids and a lot of times they’re the most connected to God,” Rasoul said. “Chill, enjoy, grow strong, play. And parents, facilitate that for your kids. Make sure your kids have good friends.”

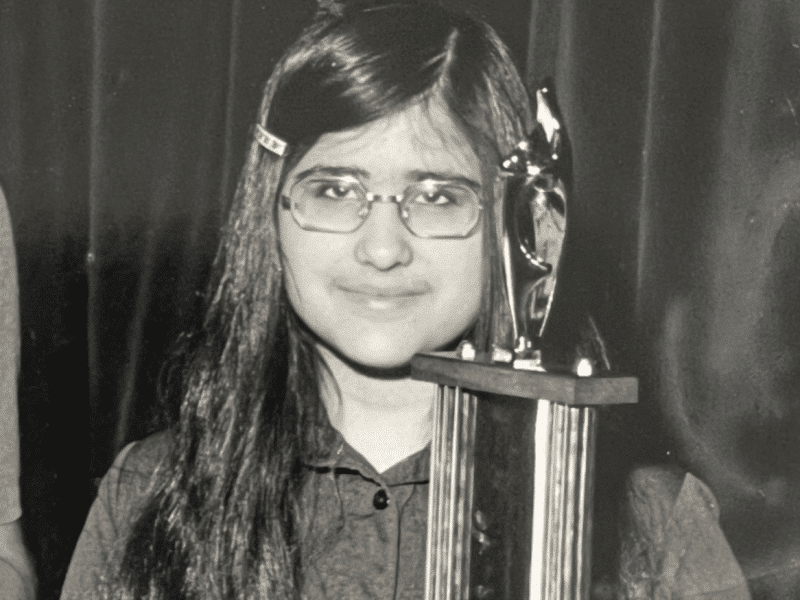

After the event, some teens without phones said it was liberating to not have a phone to keep up with. Not Myra Tahir, though, who was sitting in a corner using a laptop to catch up on her studies. A 13-year-old Marietta resident, Myra said she got her phone when she was 10. She uses Instagram for a crocheting business she started, and to keep up with her pickleball team.

“When they said not to give teens phones till they’re 17, 18, I do think it’s a bit old,” Myra said. “Because at this time and age, kids get their phones at age 10, 11. It could cause kids to have outrages and jealousy. It might be easier to give them a phone and set screen time and app limits.”

Myra’s mother, Selma Jetpuri, said her 11-year-old daughter also has a phone. “Ultimately, I don’t think 18 is feasible at all,” Selma said. “Most kids are getting their cars much earlier, and there’s so many other ways to get access to technology. I think all you can do is delay it as long as you can.”