As civil war engulfs Sudan, community members in Atlanta seek to bridge divides locally

“We’re trying to engage the Sudanese professionals, the Sudanese academics, the Sudanese intellects, the guy that runs his own small business,” said one community leader.

Isra Ghanim, a teacher at Dacula Elementary School, was preparing for her wedding when war broke out in Sudan in 2023.

Suddenly, her focus shifted from finalizing guest lists to evacuating relatives out of the country’s capital, Khartoum, and finding them basic supplies like food and water. During a temporary ceasefire, her family fled the city and made their way to the countryside. Isra’s relatives told her they eventually found themselves in a school that had been turned into a sanctuary. As they took in their new lodgings, they all thought they’d be away from home for a month or two at most.

That was three years ago.

Now, from her home in Atlanta, Isra sends money to those relatives, who have since relocated to Cairo, helping them get food and housing and education while they continue to live in limbo. Isra and her husband put their wedding—which was supposed to happen in Sudan—off for a year. They finally married in March 2024—but without any major celebration, since many family members remained stuck overseas.

For Isra, who was born in Sudan, the scattering of her family and the war’s continuation are sobering reminders of a home that remains out of reach.

“The war has literally turned my life upside down,” she said.

Since April 2023, Sudan has been enmeshed in a civil war that’s displaced over 12 million people, leading to one of the world’s worst humanitarian crises. The tensions that ignited the conflict have spilled out far beyond the region: The same tribal and ethnic divisions fueling the violence in Sudan have also followed Sudanese diaspora communities around the world, including Atlanta.

Currently, about 2,000 Sudanese people live in the state of Georgia, concentrated mainly in DeKalb, Columbia, and Fulton counties. Sudanis in the Atlanta area primarily reside in Clarkston, Stone Mountain, and Tucker. Some have come as refugees following spikes of violence in the region, while others have come on employment visas, to study, or to join family living in the area.

“Unfortunately, the Sudanese communities, in the plural, I say, of the metro Atlanta region, really mirror the chasm and divisions and the conflicts that exist on the ground in Sudan,” said Dr. Abdullahi Ahmed An-Na’im, a law professor and human rights scholar at Emory University.

285 South spoke to Dr. An-Na’im and other Sudanese community leaders in the Atlanta area, all of whom are working to mend the wounds from back home. Their approach is threefold: bringing diverse community members together, educating fellow metro Atlanta residents about the conflict—which has led to the world’s worst humanitarian crisis—and working with Black activists to intertwine struggles for liberation across borders.

Building alliances within the Sudanese community—and with other Black activists

The civil war that began in 2023 did not occur in a vacuum, Dr. An-Na’im said—it’s a continuation of violence rooted in colonialism, tribalism, and racial hierarchy.

Sudan has long endured foreign intervention and tensions along ethnic and tribal lines. The world’s newest nation, South Sudan, was born in 2011 of decades of economic, ethnic, and religious marginalization from the northern region of the country. During the war that created South Sudan, to suppress rebellion in the western region of Darfur, the Sudanese government armed a militia known as the Janjaweed—which evolved into the Rapid Support Forces, a powerful paramilitary group that’s a key player in the current civil war. Last October, the Darfur city of El Fasher fell to the RSF after a nearly 18-month siege, resulting in 100,000 displaced civilians and the mass killings of those who remained trapped in the city—members of some of the same non-Arab groups that had been ethnically cleansed in the previous conflict.

Dr. An-Na’im’s academic work proposes a solution: fostering regional coexistence as a way to overcome the country’s deep tribal divisions brought on by its colonial past. “This failure to acknowledge the root causes of the war is the reason why the war persists,” he said. “Because as Sudanese [people], we have not tended to think of each other inclusively, as citizens of the same country.”

This mistrust is also reflected in the diaspora—including in Atlanta, where multiple Sudanese groups, divided by region and tribe, live separately from one another, said Dr. An-Na’im. For years, Dr. An-Na’im and other community members have been working to establish a space for all Sudanese people, regardless of ethnicity or tribe, to come together—like during iftars in Ramadan. But even that’s been hard: “Each time we try to bring people together, [to] just come for [iftar] so that we can all talk socially, people are not willing to do that,” he said.

Dr. An-Na’im says he understands why this mistrust exists and how it is a remnant of decades of systematic disenfranchisement and oppression of specific ethnic groups. However, he also believes that a united diaspora makes a liberated Sudan for everyone all the more possible. “We try to reach out to various factions or groups to say, look, it doesn’t make sense really, to continue reliving the war abroad in these very negative and destructive ways,” he said. “But still, people are not willing to engage.”

It’s an ongoing effort. Smah Abdelhamid is a public health professional and has been a member of an organization called the Sudanese Community of Georgia since 2019. The organization helped newly arrived Sudanese immigrants and refugees with housing, food, bill payments, and social support before officially registering as a nonprofit in 2021. Smah emphasized that the group was created by Sudanese people, for Sudanese people—of all backgrounds, professions, genders, and tribes.

“We are trying to engage all of the community, not just the new refugees,” Smah said. “We’re trying to engage the Sudanese professionals, the Sudanese academics, the Sudanese intellects, the everyday person, the guy that runs his own small business, you know, and trying to create a core where we could provide even further support for one another.”

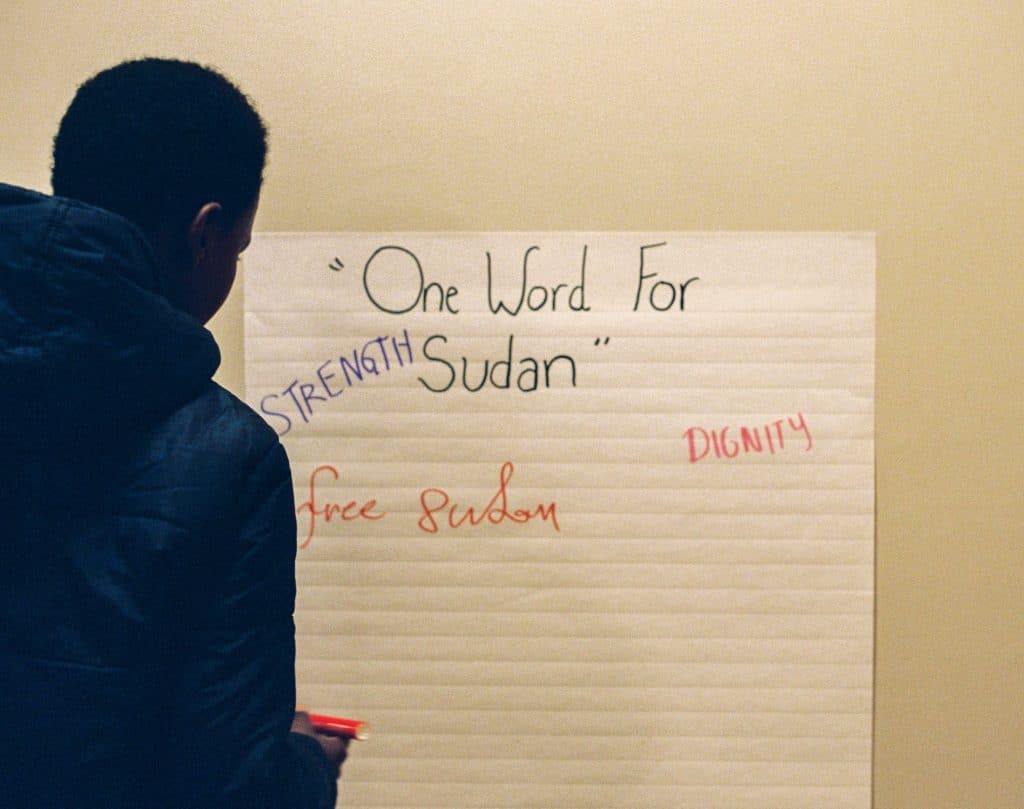

As the war continues into its third year, and as Smah and other community members try to reconcile disparate Sudanese communities in the Atlanta area, they’re also in the beginning stage of forming a coalition for Sudan—a place where academics, existing organizations, and community members can amass resources and political power for Sudan. The coalition met twice last month. The group is developing plans to raise awareness through university teach-ins and press conferences as well as to push for political advocacy by meeting with Georgia politicians in the upcoming 2026 legislative session.

Another goal of the coalition is to build stronger relationships between African diaspora and African American communities in Atlanta. Coalition member Dr. Jared Grant, a professor at Clark Atlanta University, said this kind of advocacy reveals a broader fight for justice for marginalized people: “While we’re not monolithic, we have a monolithic problem, and that monolithic problem is global white supremacy.” Atlanta’s unique position as a Black capital and its long history of human rights movements—from the civil rights era to the push to end apartheid in South Africa—makes it an ideal place to organize for Sudan, he continued: “Atlanta has always been very central, and the Blacks in Atlanta have been very central in Black movements. So it would only make sense that we would be a part of this movement as well.”

As advocacy efforts continue to take shape in Atlanta, community members we spoke to seem to agree on one thing: their voices should be central to any discussions about their country. Doha Medani, a local organizer for Georgia for Sudan and board member of Decolonize Sudan. She says that Sudan’s trajectory has long been affected by the political interests of warring factions and international powers. “There’s so many people that think they have a say over Sudan, and it’s not because they care about Sudan. It’s because they care about Sudan’s natural resources,” she said. “What we’ve been seeing the past five years has been other people’s agenda for Sudan, and not that of the people.”

Alongside the coalition, Doha hopes to continue organizing through Georgia for Sudan, a grassroots initiative looking to raise awareness of Sudan’s war through community engagement and art. The group is working on a zine that will highlight Sudanese artists and writers with a variety of perspectives to highlight the diversity of Sudan’s identity and inspire dialogue. “There’s a lot of differing opinions right about how to get to the future that we want,” she said. “I would like to hope that the future that we all want is one where anyone who calls themselves Sudanese can live freely and justly. But that’s not going to happen without a lot of conversations.”

Despite not having been able to visit for several years, Doha’s memories of visiting Sudan during her summer breaks, before the latest coup broke out, haven’t yet faded. She described that in the summer months, Sudanese families like hers would often sleep outside as the night cooled—drinking tea, chatting for hours, and staring into the sky. Some mornings would bring strong gusts of wind that kicked dirt and sand into her and her cousins’ eyes.

Like Isra, much of Doha’s family is now scattered across the region. Her cousins from those sleepy mornings are now living in the Gulf. Doha says they reminisce often about those nights.

“Those were very formative moments, just being outside, literally sleeping at night outside, and looking up at the moon—those small things of being in your own country, on your own land, just feels very beautiful,” she said.

“What we would give to wake up with sand in our eyes.”