A group of Latinx and Indigenous photographers set out to document the challenges of getting around Buford Highway without a car

Now, they’ve published their first ever photo book.

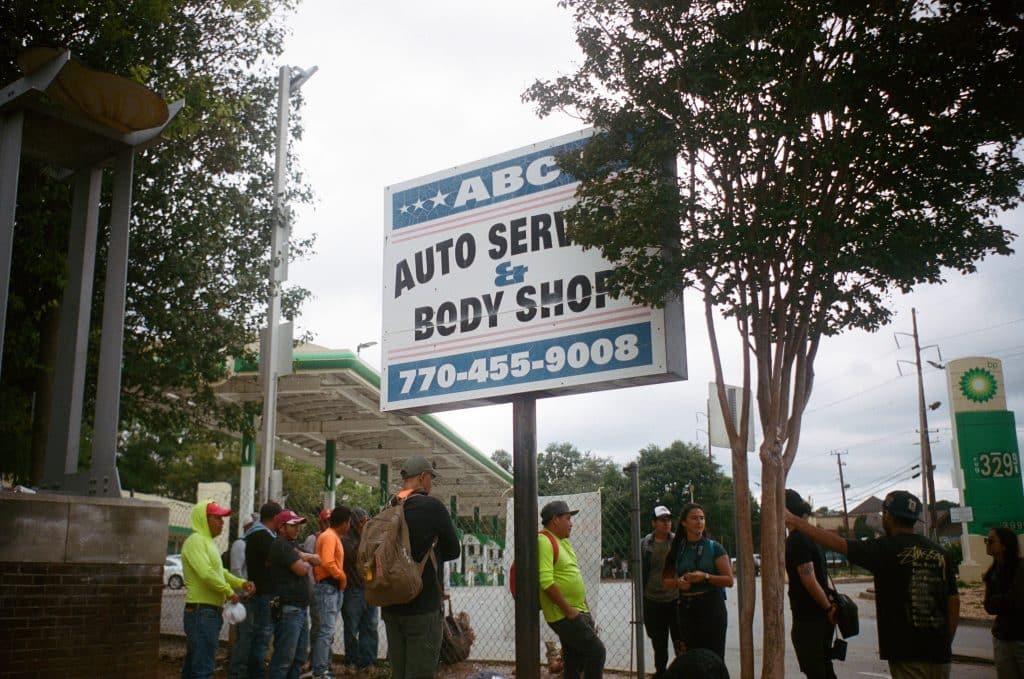

“In different parts of Atlanta, if you have a car, you have a city that’s built for you,” Victoria Garcia said to a young man from Central America, standing alongside other men at a gas station on Buford Highway, waiting to be picked up for a day job. “When you’re in your car, you don’t have to worry,” he told her. “But when you don’t have the option of driving in a car, everything is more dangerous.”

Victoria, the co-founder of a local photography club, had come to the site to capture people’s lives in the neighborhoods around Buford Highway and was interviewing the man as part of We’ll Get There No Matter What, a photo book released on February 1 by Captura—a photography club for Latinx and Indigenous photographers—and Highway Inmigrante, her ongoing personal project to document life on Buford Highway. The book, which includes interviews with area residents, as well as 88 pictures by 16 photographers, is an effort to capture the reality—and challenges—of moving around on Buford Highway, depicting scenes like men walking to work, families going grocery shopping, and people carrying laundry by hand to the lavandería.

For those without a car in the area—a significant population, considering the large undocumented communities living in or around Buford Highway who are not permitted to get driver’s licenses in Georgia—getting from one place to the other can be dangerous. The highway, six lanes wide in some places, is recognized as an immigrant destination with over 1,000 immigrant-owned businesses; it’s also known nationally for its pedestrian problems (it was featured in a PBS documentary about pedestrian safety in 2010). It lacks safe places to cross, bike lanes, and even sidewalks in some places. Local news regularly features reports of pedestrians injured or killed by drivers on Buford Highway.

The Captura photographers are between 18 and 35 years old, come largely from Latin America, and most were “either immigrants or children of immigrants,” said Victoria, who was born up in Gwinnett County but grew up around Buford Highway, and whose father is from Mexico. Capturing life on Buford Highway “was meaningful to a lot of them.” This was the first time, she said, the photography club had embarked on a project that addressed a social issue (their past work was more technical, she said).

So last fall, fueled by funding from Smart Growth America for the project, photographers walked up and down the highway. One walk started at City Farmers Market in Doraville near the intersection with Chamblee Tucker Road; another made its way up Chamblee Dunwoody Road while, for the other, photographers walked to the Doraville MARTA station, where they boarded the train down to Chamblee and took pictures as they walked to Plaza Fiesta.

“As we started explaining to some people what we were doing, more and more wanted to listen,” she said. “You could see them looking through the fence, and when we told them what we were working on, they kind of shared their own reflections.” One man said that his son back in Nicaragua wanted to be a photographer, and that he worked hard to buy him a camera so he could practice.

People of color, Native Americans, and low-income people are at higher risk

Data in a report on pedestrian safety put together by Smart Growth America found that Black people are killed while walking at more than twice the rate of white people, and Native people are killed at over four times the rate of white people. People walking in low-income communities die at higher rates and face higher levels of risk compared to all Americans. But the report had a missing piece of information, Victoria and the team thought.

“From our perspective, something that wasn’t really addressed in that report was the legal status,” Victoria said. “That’s a perspective that we were able to bring to the project that the other grant awardees did not touch on. They did say that they think Latino people are very underreported, and part of that underreported is that immigrants fear the police, so if you do get hit by a car, or if you do face some injury or don’t feel safe, you don’t report it.”

As a result, by putting together the photo project, Captura was able to bring a unique perspective to the conversation of transportation inequity, while at the same time, showing powerful stories behind the people they photographed.

But it was also an opportunity for the photographers to reconnect with their backgrounds.

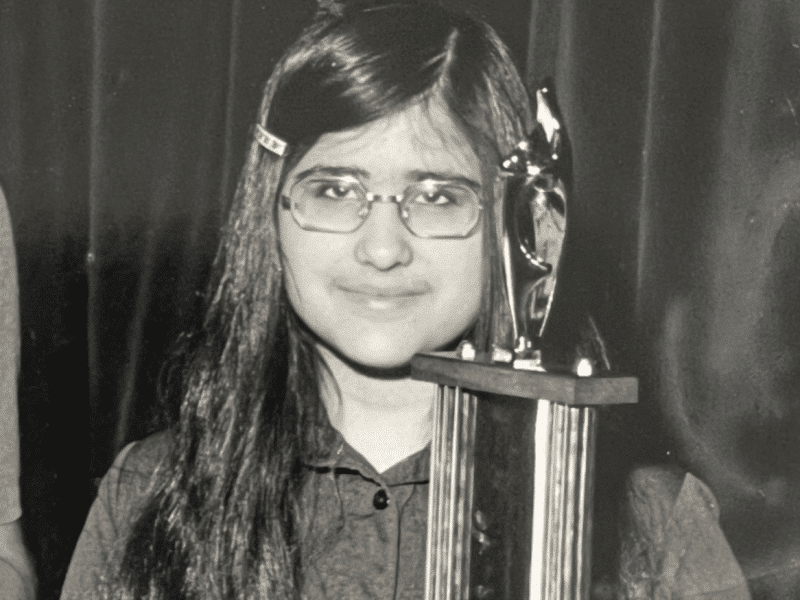

For Vianey Cecilio, the cofounder of Captura, creating the photo book was also an opportunity to reconnect with her immigrant background. Born in Mexico, she was brought to the U.S. by her parents when she was less than a year old and she was only able to get a legal status when she was in late elementary school.

“I had forgotten my own background since I’ve been documented, since I was in late elementary school,” Vianey said. “On the second photo walk, in particular, seeing the dirt paths for me, I’m like, Oh yes, one time I was young too, and I had to walk those dirt paths with my family when we had no car here in the United States. So it was a lot of reminders of my origin”

Those interested in purchasing the photo book can email Captura at info@captura-atl.com. Follow the club on Instagram to learn about upcoming events.