Fearing deportation, some metro Atlanta residents ask: Who will take care of my children?

An Atlanta attorney says interest in power of attorney—an arrangement for parents to sign custody of their kids over to a trusted guardian—has surged since Donald Trump took office. But finding a guardian isn’t an easy task.

*Read this story in Spanish / Lea esta historia en Español

In December, Maria received a phone call from a friend in Florida asking an unexpected favor: Her friend, who doesn’t have legal residency documents, feared that she would be deported back to her home country of Guatemala by the incoming Trump administration. If worse came to worst, she wanted to know, would Maria take custody of her children?

Maria is a naturalized American citizen living in Cobb County, and already has her hands full with three children of her own, ages nine, 13, and 14. But her legal status in the U.S. put her in a good position to care for her friend’s 13-year-old son and four-year-old daughter—so in January, Maria signed a power of attorney, a document that established her as an emergency guardian for one year in the event that her friend or her friend’s husband are detained or deported. “It was a tough conversation,” Maria (not her real name) told 285 South in Spanish. “But I immediately said yes, because it could be me asking for that favor.” Though she has citizenship, Maria—who is also from Guatemala—feels vulnerable these days, in light of immigration crackdowns affecting even those in the country with legal documentation.

Maria and her friend aren’t the only ones making plans for their children. President Donald Trump took office in January with promises to conduct the “largest deportation operation in American history.” So far, the numbers have been difficult to track, with one expert telling 285 South recently that deportations under Trump may not be higher than under his predecessor, Joe Biden. But the threat of them, combined with high-profile raids and other enforcement actions, has compelled many people, especially those without documentation, to prepare for the worst. In Atlanta and across the country, immigrants are making plans for their children to be looked after in the event they’re deported.

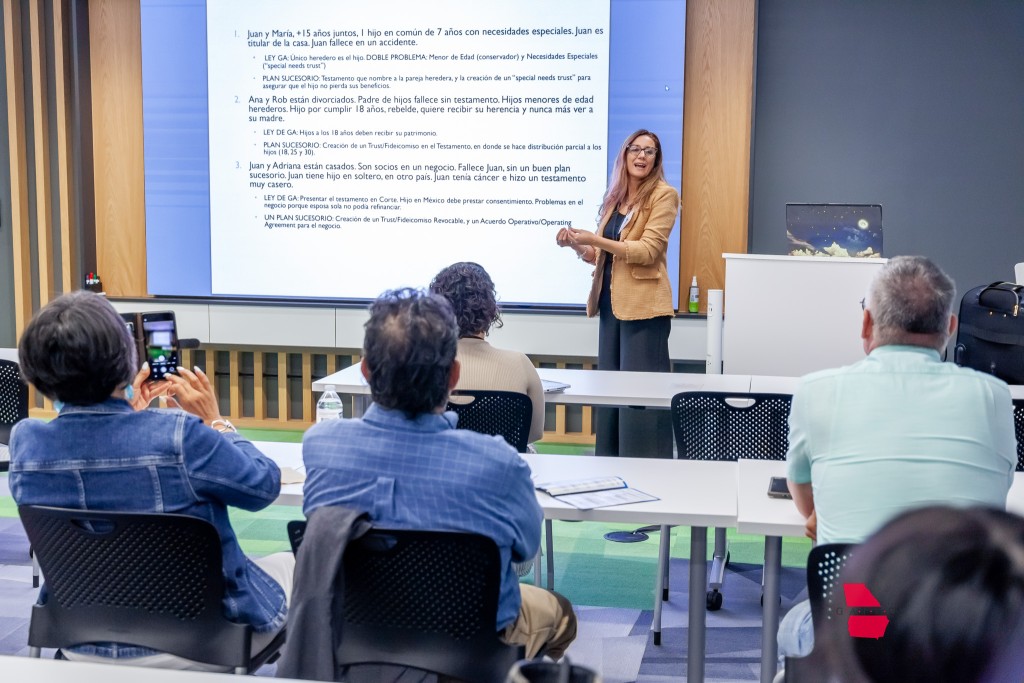

Since the beginning of 2025, the Atlanta-based estate planning attorney Pia Candotti told 285 South, she’s had twice as many people as last year—both undocumented and documented—contacting her about setting up power-of-attorney arrangements for their children. Many were people who came to her last year for a consultation, finally showing up and saying, “Now it’s time to do it. I don’t want to procrastinate more.”

For most families, the first step is finding the right person to volunteer to take custody of their children. But many get stuck at that step. “Most of the people don’t have anyone to leave their kids with,” said Cristina De la Cruz, cofounder of Amigos de la Comunidad, a local organization that has been helping local families understand the power-of-attorney process and connecting them with Pia Candotti. Those people might not know anybody else with legal status in the U.S., she said, or may not have the means to pay for the power of attorney, which can cost around $150. Or the potential guardians may not be willing to undergo a background check.

It’s not essential that a guardian has legal status, Pia said, but it can give more stability to the child. “I know sometimes, and this is a real challenge that we have in our community, [parents] say, ‘The rest of my family doesn’t have legal status. So what?’” Pia encourages people not only to think about family but also anybody else who would be willing to help and whom they trust—teachers, for instance.

Still, though, some families have had teachers offer to act as a temporary guardian, Cristina said—only to back out once they realize what a huge responsibility it would be. So far, only five families out of ten who have contacted Amigos to connect with Pia have been able to find a guardian. (Most of those interested in pursuing such a path come from Guatemala or Mexico, she said.)

In any event, schools should have a copy of the power of attorney with the contact information of the guardian listed on it—so that, if the parents are deported or detained, the school can call the guardian instead of a social worker. For that reason, the guardian should also be somebody who lives nearby. (If parents want to delegate the responsibility of care to older siblings, they just need to be 18 years old—the case with anybody assuming guardianship.) Many Hispanic families, Pia said, have older children with DACA status, in which case she recommends two powers of attorney: one person with a legal status in the country and a second for a family member that is close by and committed to act as guardian in case of an emergency.

Power of attorney may look a little different for each family, Pia said, but what it gives to everybody is time: “It is a legal tool to give them time to plan further ahead, while making sure that someone is taking care of their kids.” Parents worried about deportation, for instance, can make plans for their children to join them in the country they’re deported to, or they can decide to legally designate a permanent guardian by a court. “I know it’s a challenging time, but I would say the positive part is to take advantage of these legal tools,” Pia said. “It doesn’t matter the legal status—they’re available to everybody.”

For Maria, her friend from Florida was somebody she’s known for a decade—they worked together in the field as farmworkers, and have spent many summers together with their children. “This is an act of love, knowing that a person is going through this situation and having that kindness in your heart,” she said. “It’s simply about making things easier for those mothers. We have to put ourselves in their shoes: What would happen if it were me?”